Charles Nimmo

47 years, New Zealand

7 INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT HYPOXIA

‘Unusual causes of low blood-oxygen levels, and coping strategies, learnt from conducting simulated altitude training.’

INTRODUCTION.

Those who engage in mountain pursuits do it for a variety of reasons, some wish to push the limits of human performance by climbing a 7000m peak without bottled oxygen, and others have less lofty but equally fulfilling goals, like trekking to spot a Snow Leopard in Tibet. Regardless of the goal, the more you understand how an alpine environment affects your physiology, the safer and more enjoyable your adventure will be.

To understand how your body will perform, it is best to first look at the constants, then the variables.

What are the constants? The higher you go up a mountain the less oxygen you get per breath, this is because the lower atmospheric pressure means the molecules in the air are further apart. The inevitable result is that your blood-oxygen saturation (SPO2) will be reduced. The lowering of your blood- oxygen below a certain point will start to affect your fatigue levels, your fine motor skills, and your cognitive (decision making) processes. And to put it in the simplest terms, low blood oxygen is the precursor to suffering from mountain sickness. A healthy person at sea level will have an SPO2 of 96-99% as measured by a device called a Pulse Oximeter. How much your SPO2 will be reduced depends on the variable factors.

What are the variables? They are almost too many to list, however it is best to say that your unique physiology, current state of health, and climatic conditions will create individual variation in your response to a low oxygen environment, and high altitude.

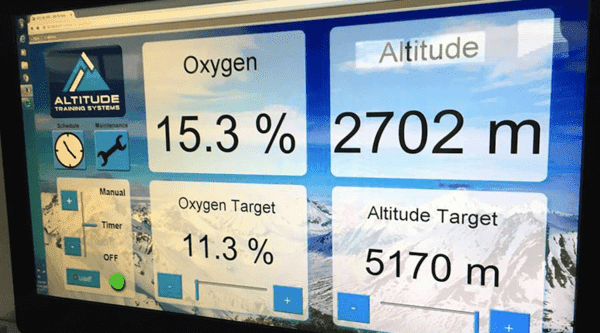

If your individual response to low oxygen is so variable, how can you predict how you will respond to a high altitude environment? It is well recognised that there is a huge amount of individual variation with how people respond to being at high altitude. It is generally recognised that age, sex and fitness are not good predictors of whether you are susceptible to mountain sickness. However, while running a Simulated Altitude Training facility in Christchurch New Zealand, I have begun to see some curious patterns with peoples' response to a hypoxic (low oxygen) environment. To better understand things that may cause you, as an individual, to loose blood-oxygen, is to be better equiped.

Before we begin I must add the caveat that a simulated altitude environment does differ from a high altitude environment with respect to temperature, and air pressure, however it does provide the perfect opportunity to test different scenarios, and variables, in a hypoxic environment. You may wish to debate how much these phenomenon transfer to a real world setting. Recommendations should therefore be taken with a grain of salt, maybe even Pink Himalayan Rock-salt.

WHAT HAVE WE DISCOVERED SO FAR?

1. Loose lips, sink ships. During World War 2 a British propaganda campaign tried to educate the populous that idle chit-chat could lead to troop deaths, if overheard by the wrong person, hence the term ‘Loose Lips, Sink Ships.’

In the Altitude Training Room, we freely observe how much talking affects your blood oxygen levels. Once we get above 4000m, motor-mouths can find themselves on the back foot very quickly, because they are not intaking enough oxygen. You should develop your own strategy when trekking to be aware of how much you talk, and if your are getting enough full breaths.

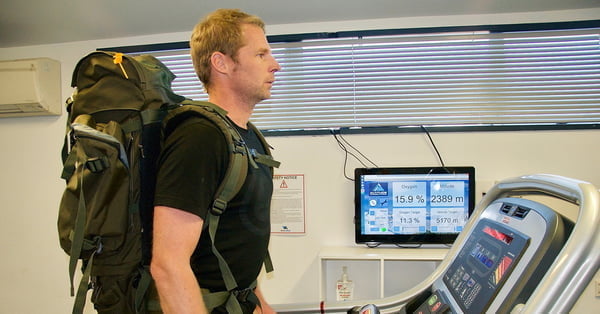

2. You can get drunk on water (sort of). Yes, there is a right way to take a drink from your drink bottle to avoid the drunken state that hypoxia causes. We have a special training methodology (more on this next instalment) to acclimatise people to exertion at high altitude. The final stage of the training will be to have the individual walking on the treadmill, with an steep incline on, and a back pack, at 5000m+ equivalent. The aim of the game is for them to hold a blood saturation of plus 80%. Those who grab their drink bottle and chug while charging along will find themselves at 70% SPO2 in a flash. The strategy we teach is to; first acknowledge that you need a drink, then stop and take three slow, deep diaphragmatic breaths, next you take a decent 3 gulp drink, then take three more deep breaths and carry on, works a charm.

3. Watch out for twitchy people. This phenomenon is not present in research literature but when it does remember that you heard it here first. Are you more of a sprinter or an endurance type person? It is recognised that sprinters have more fast twitch muscle fibres, and endurance athletes are more slow twitch dominant. Fast twitch dominant people appear to be more susceptible to low blood-oxygen levels. Our observations suggest that if you are heavily muscled, and more of a sprinter, then you have more oxygen hungry muscles. The first time I observed this phenomenon I had two top rugby players from the Pacific Islands in the altitude room. The Pacific Islands are famous for providing athletes who weigh over 100kg/220lb, who incredibly can run an 11sec 100m. No-one likes standing in front of that sort of momentum. In the booth at the same time was a slightly built Irish labourer who had won his membership in a competition. He had not exercised for 6 years and smoked persistently. The Rugby players SPO2s had dropped into the 70s, while the Irish labourer was in the high 90s. More research is needed on this phenomenon, however anecdotally we see a pattern emerging.

4. Sleep, stress, and fatigue, are powerful forces. We are not sure of the physiological mechanisms, however, your quality of sleep can affect your ability to handle hypoxic conditions, as can stress and fatigue levels. Our most dramatic anecdote was with a lady we consider to be our most altitude-adapted athlete. She has the ability to do rather high intensity exertion in over 5000m simulated altitude. After a string of earthquakes in Christchurch, she came into the altitude room feeling stressed and having not slept properly. For the first time her SPO2 dropped to 81% and she was only walking at 2900m equiv. We see and experience this phenomenon a lot. If you are pushing for a summit and your are suffering from the aforementioned issues, then you should be extra vigilant of the effects of altitude on your body.

5. Lazy breathing. It seems silly, but we are often teaching people to breathe. Shallow and inefficient breathing will put you on a sure path to low blood-oxygen levels in a hypoxic environment. It is best to practice efficient breathing till it becomes second nature, and you better develop the intercostal muscles in your diagram. In the altitude room we get instant feedback on how efficient your breathing is. Using the pulse oximeter you can gratifyingly watch as your blood oxygen is restored.

We teach that when you breath, your stomach should project, followed by your chest, and you should draw from your nose and mouth simultaneously. When learning to breathe, you should try to find a little more lung space each time you breath, in order to build lung capacity and efficiency.

6. Bugs and hypoxia don't mix. When someone is training while unwell their SPO2 is very susceptible to drops. In fact I can attest that when I am sick and in the Altitude Room I practically want to claw my way out, as it exacerbates whichever symptoms I am experiencing. Be very aware if you are heading to altitude while suffering from an illness.

7. Hypoxia causes Euphoria. Twice a week we have what we call Happy-Hour in the altitude room whereby we take the simulated altitude up to 5400m. With the Altitude Room full of hypoxic mountain and adventure type people, the banter can start to get silly. Each person has strict instructions to manage their SPO2 levels, however some people will go into a slightly euphoric state and happily let their Blood levels drop, forcing me to intervene. This is an actual conversation. “Hey Charles I’m at 72%.” Cam says with a magnificent grin. “Cam I told you, not to go below 80.” “Haha, I know.” He replies, still with a stoned looking smile on his face. So be aware, hypoxia induces euphoria, and euphoria has a deleterious effect on your judgement. If you feel particularly jovial in a high altitude environment, keep yourself in check that you are making sense when you talk, that you are making sound judgments, and are in full charge of your faculties.

CONCLUSION.

The first rule of thumb to take away, is that hypoxia amplifies your current status. The second rule of thumb, is to not get hung up on rules of thumb. Your physical response to hypoxic conditions is very individualised, and very situational. One must be prepared to change your strategy as situations change. The fact that there is so much variation can actually be a reassuring thing for some people. We have trained people who have had mountain sickness in the past and are afraid that they are susceptible to it, when in fact, another variable, like a virus, had caused their susceptibility and they are perfectly ok to proceed to altitude.

Author: Charles Nimmo.

Vertex Altitude Training.