Last update:

Mountain Planet

(18/03/2016)

Sergey Kofanov

47 years,Australia

8 years ago

MOUNT COOK CLIMB REPORT

Mount Cook (3724 m) is the highest peak of the Southern Alps (New Zealand) with a very photogenic profile, which is often used by Hollywood film crews as a K2 "stand-in" (watch "Vertical Limit."). The easiest route to the top is a Grade 4 in terms of its difficulty that means “technical climbing” and requires knowledge of how to place ice and rock gear quickly and efficiently. In addition, there are several routes of the fifth grade. All routes on Mount Cook are mixt routes, that means working both on snow&ice&rocky terrain. Normally, climbers get to the starting point of most of the routes by helicopter (to the "Plateau Hut"). The flight takes about 20-25 minutes and its organization isn't difficult, since there are several helicopter companies in the mountain’ nearby.

You can get to the shelter by walking, but it's a two-day walk on a very difficult terrain and implicit path. Personally, I know guys who gave up the expedition only because they were not able to get to the starting point. The fact is that the glaciers in New Zealand faded so much over the last 20 years, that the majority of tracks that have been laid on the moraines, just vanished. Now, some shelters are not visible from the trail, and often, to get to them, it is necessary to overcome a 200-300 meters of steep and loose slope. In addition to a difficult terrain, climbs on Mount Cook are often interrupted due to drastically changing weather. According to the employees of the national park, in the best case, only one of three forecasts comes true. The ridge is located only 20 km from the coast and it is not surprising that it attracts all the storms coming from the Pacific Ocean. The climbing season officially opens in late November and ends in late February, but it reaches the peak of climbs in December. January is not considered to be the most favorable time for climbing, although it’s a middle of a summer. This is due to the fact that the classic route runs along a very crevassed glacier, which in January often becomes almost impassable. All the snow bridges melt, and the practice of using aluminum ladders is not an option here comparing to the Himalayas. Some groups try to climb during the last two weeks of February, when the crevasses are closed by snowfalls, but such attempts are not conducted every year.

To be precise, I am trying to climb the Mount Cook since 2004. During this year, I was at the foot of the mountain, for the first time, with a team, which included a few world climbing celebrities - for instance Evgeny Vinogradsky (6-time Mount Everest summiter) and Alex Abramov. It was early November, although the official climbing season on Mount Cook was going to start only in one month, we spent those days, dedicated to the climb, close to the helipad waiting for a weather improvement. The miracle did not happen. It rained for a week, the mountain was covered by dense clouds and the maximum that we were able to do was going on a few hiking routes in the surrounding area. Over the past few years I had two or three chances to organize an expedition to Mount Cook, but every time something went wrong. Last year, my good friends from Kazakhstan invited me to their expedition to Mount Cook. Our team was very strong, all the participants had a background of climbing Mount Everest and Mount Denali, so we decided to plan an expedition during the favorable January, and thought that we will manage somehow the passage of the glacier.

On January 16, all three members of the expedition met in Christchurch. From this point, we moved to the Mount Cook village by car. We planned to start the mountain route from walking, without having to waste time on pre-acclimatization. In 99% of cases of mountain climbing the classic route takes place in one day. Normally, teams start from the "Plateau Hut" shelter at 2 a.m., face the glacier route during the coldest moment, and at dawn reach the summit rocks, which takes them to the top of the ridge. This part of the route takes about 6-8 hours, and in the evening groups come back to the shelter. By this way, they spend about 20 climbing hours during such routes. But, these time limits apply only to those groups that are accompanied by local guides which know all the nuances of the route. Our climb was recreational, we were there for the first time, so there were small chances to meet the specified guides "norms." In this regard, we originally planned to take the route with an overnight stay, which determined the starting weight of our rucksacks, amounting to about 20 kg each.

Three days before arriving to New Zealand, on a daily basis, I began to ask information to the helicopter pilots about the weather forecast for the planned departure date. Each time I was getting the cautious response that "the chances are quite high." We considered weather changes and originally included some extra time to expedition. By this way, we planned to do some acclimatization in the surroundings of the mountains in case of bad weather. As a result, we spent 3 days near the airport, sitting on our backpacks in a constant anticipation of departure. Below the sun was shining but Mount Cook was covered by a dense cloud, which used to raise slightly, then to drop a little, but there was no way for the helicopter pilots to make a safe landing on the glacier near the shelter.

Finally, in the evening of the third waiting day, meteorologists gave us the green light to fly. We loaded quickly our rucksacks on the helicopter, and after half an hour were already boiling water in the spacious shelter kitchen "Plateau Hut."

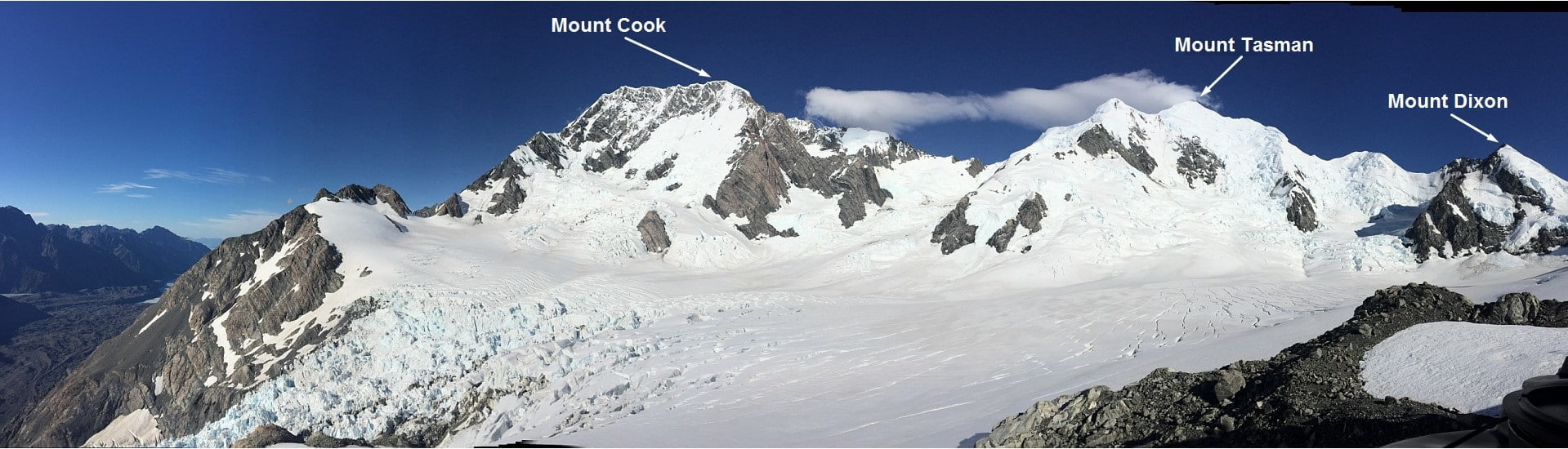

The hut is equipped with a gas stove, two toilets, solar panels, kitchen utensils, a radio station and a few rooms, which can easily accommodate up to 30 people. You can’t book the hut in advance and it receives those who arrive first. All the necessary national park visit forms can be filled at the helicopter company before departure as well as in advance at the Mount Cook village information center. We paid the hut after finalising the expedition. There is a place for 5-6 tents next to the hut, for those wanting to save some money, and for those who don’t fit inside the hut. We were the only group on the mountain, so we occupied the entire hut by choosing the most comfortable room. Rain did not allow us to orient and we only saw the lower part of the glacier, and some sort of trail that starts from the hut and left in the direction of whether the Mount Cook, Mount Tasman whether, or Mount Dixon.

Before sunset, we walked a bit on the glacier, but did not understand in what direction was the peak. Fortunately, the weather forecast for the next few days was good, so we went to bed after planning to start in the early morning. At seven in the morning we have already started moving on the glacier and planned to get to the sleeping point before lunch.

The glacier was badly broken. In some places it was guessed trail, but often it ended abruptly at the edge of the crack next to the collapse of a snow bridge. In poor visibility, our ascent could become a walk on the glacial maze, but fortunately for us, the sky was cloudless, the glacier was well looked far and wide, so finding the way did not took long time.

It happened only two or three times that I had to take off the backpack and go "beyond the horizon" for the rest of the rope in search of a passage between the cracks. In any case, I had a GPS, which properly recorded our zigzag route. Somewhere for dinner we got to the top of the glacier, which overlooks the rocky part of the route, unexpectedly we found a really problematic place. A huge crevasse crossed over glacier entire width, the old trail ended abruptly at the edge of the 10-meter precipice, where earlier apparently was snow bridge. Right in the rock glacier rested out and go, we did not want to, because there is always hung multi-ton blocks of ice, and left it broke off a huge icefall, where we would be put even less. But the chances of finding safe passage there were higher, so we went along the edge of the crack to the left and it has paid off.

After about 500 meters we came upon a huge serac, which fell on the opposite edge of the crevasse and formed a very narrow bridge, to overcome which was quite real. I gently passed without a backpack on him, fastened the rope to the other side, and we all took turns, one after another moved through the crevasse. Somewhere in an hour we came to a narrow and shallow part of the glacier, where you can safely break camp. In fact, this is the only place of the route where there is no risk that you will come an avalanche or fall ice collapse.

The site is located in a snow trough, well protected from the wind by rocks, and can comfortably accommodate two or three tents. Before installing the tent we checked the whole area avalanche ramrod, making sure that we do not have a single crevasse. In the rapid set up camp and had a snack. We decided to light up to the rocky part of the route to trodden tracks, which we had to go the next night. On the way to the rocks it is one of the most unpleasant places of the route because of its hanging ice-fall, called a "gun barrel" Groups try to take this place as quickly as possible, and late at night, until the icefall "sleeps". We treaded tracks up as much as it was safe, and in the evening descended into a tent to rest.

We planned to leave our tent at four o'clock in the morning, after I requested an update of the weather forecast, which promised a good day in terms of visibility and wind. We woke up at three in the morning and we heard the rustling of a nasty snow on the surface of the tent. I came out ant found a dense overcast hanging that slowly covered our track with snow. However, things didn’t look so bad as the received six hours ago weather forecast warmed our confidence, and we left at four o’clock in the morning, as planned. The snow was increasing according to the altitude, but for the time it did not create us problems as our footprints were easy to find, the relief was simple and at six in the morning we got to the rocks and to the traverse which lead us to the summit ridge. We kept working in coordination, by traversing a snow slope on its very edge, where it connects with the rocks. It gave us the opportunity to always keep at least two or three belay points for a rope, sometimes by using snow bars and often by using cams and stoppers, which we used to laid into rock cracks. We crossed the slope by using front teeth with two ice tools in our hands. At first we worked at full rope, but gradually reduced the distance between each participant up to 15-20 meters, as the growing wind simply "blew" our teams, and visual contact was limited to 5-6 meters. By seven in the morning it was already quite light, but it is better to us from it did not - quite the contrary. At sunrise the temperature rose and was kept somewhere in the vicinity of zero degrees, so the snow falling on us first melted and then gets frozen in the ice shell. By eight in the morning we finished work on the traverse, and climbed to the bottom part of the summit rocks, where the summit was somewhere 350 meters above us. Next, we had to work on rocky terrain, which as a whole was not difficult, but on the way down to the bad weather conditions, could turn into a trap in which we could get stuck indefinitely. Despite the fact that all the clothing we had was made from high-quality gore-tex, we were soaking wet - boots and gloves squelched water, backpacks were covered with centimeter layer of ice, and our iced rope became as thick as a ship's rope. We had a couple of dry ropes in our backpacks, but judging by all indications, the weather was not going to improve - the snow was falling from the sky, so that the last man on the rope did not see traces of others, and each stop was fraught with hypothermia.

Finally, we decided to turn around because the situation began to go out of control. The climb down to the tent took us no less time than climbing up. The cracks we put the stoppers in at night, were covered with ice, snow pellets whipped our face, we stray from the path, and sometimes had to dig snow slope in front of us to find our tracks. However, by noon we were safely down to the snow-strewn tent. We decided to continue the descent, because we do not understand, for how many days the storm came, and there were no chances to dry our clothes sitting in a wet tent. Scattered on backpacks camping equipment and sipping hot tea, we continued our climb down the barely noticeable trail that suddenly broke off at the edge of a huge crevasse. Just yesterday we crossed it on a huge serac, however it is disappeared, depriving us of the opportunity to move to the opposite side.

The situation was out of control. We absolutely didn’t want to wander in search of a rush down the glacier to break with zero visibility. We also didn’t want to stay in the same place as we would start freezing soon. Fortunately, at that moment, the clouds rose by several meters for a couple of minutes, and we noticed that somewhere 500 meters away from us, a crevasse was resting on the rocky outcrops, where between the ice blocks we were estimating a passage to the lower part of the glacier. In more favorable conditions, we would never get through that ice-fall, but there wasn’t another way to move through. As a result, we began to actually move along the crevasse by touches, looking for a place where we could go down the rappels with its higher margins and a pendulum swing in the opposite direction. After that, we found a place that was the only one where it was possible to turn the focus of this. Going rappels on the other edge of the crack, we even tried not to breathe, so as not to disturb hanging over our multi-ton seracs. There still wasn’t visibility, and in addition, now we lost our trail, so that the route had to be laid again, blindly wandering between the huge crevasses and shaky bridges. At some point, we just stopped, not knowing what direction we should move to. The area was completely unfamiliar, the tips of our fingers begun to lose sensitivity, and water in the shoes squelched louder and louder. At that moment I remembered that I had a GPS in my backpack, which properly recorded our entire route. It turned out that we were only 30 meters from our tracks, which direction was in a way we would never thought about. From then it was easy to move along the trail, we began descent quickly and at some point cloudiness was already above us. The hut was already visible at the bottom. It was about 5 o'clock in the evening, and we even got a satellite phone and called the helicopter pilots with the hope that they would pick us up that evening. Unfortunately, we were informed that the helicopter had already made two attempts to land today near the hut, but the gusty winds did not let them do it. The next morning looked more calm in relation to the wind, so we were ready to spend another night on the mountain in terms of the relative shelter of comfort. As a result, the helicopter still took us the next day, but the mountain was closed by snowy clouds, and remained, in spite of any forecasts. We finally escaped with slight shock and frozen fingers.

If you got to this point, you deserve some extra advice:

1. Try to plan your expedition for December;

2. Use the services of local guides;

3. If you decide to go on your own as part of a recreational climb, then choose the option of spending the night in the middle of the route;

4. Do not count on the weather forecast, always be prepared for the fact that after 6 hours it will change to the opposite;

5. Have a ski mask, it’s very useful in conditions of strong wind and snow pellets;

6. Finally, take care of yourself and do not prioritise the climb price instead of your health.

PS: check our gear list in the profile of our expedition (you need to be logged in to see it).