Trekking News

6 years, Australia

Trekking Through Fire and Ice on Greenland’s 102-mile Arctic Circle Trail

Late on my fourth day hiking the 102-mile Arctic Circle Trail in western Greenland, I encountered smoke rising from the ground. White tendrils, sometimes columns, rose in all directions from charred soil and wisped out from an 800-foot-tall hummocky, granitic hillside to my left. To my right was the 14-mile-long, string-bean-shaped Lake Amitsorsuaq, the biggest of the dozens of lakes we had hiked past since starting the trail. The smoldering ground extended to the lake’s shore and made the supersaturated blues of the water pop even more.

On the Arctic Circle Trail in Greenland, the 14-mile-long Lake Amitsorsuaq makes for a scenic spot to drop the gear. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

On the Arctic Circle Trail in Greenland, the 14-mile-long Lake Amitsorsuaq makes for a scenic spot to drop the gear. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

While it was plausible that we had wandered into an area dense with steaming thermal features, we hadn’t. Me, my boyfriend Derek and our friend Larry had finally reached one of the wildfires that made international news when they started a few weeks before our 2017 trip.

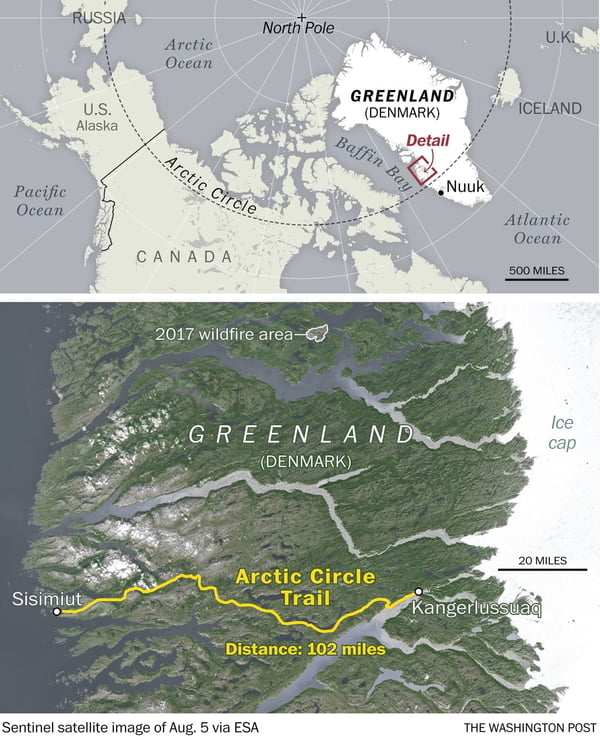

When Larry approached Derek and me about doing the long-distance trek between the small community of Kangerlussuaq and Greenland’s second largest city, Sisimiut — population about 5,500 — we said yes before looking at any maps or photos of what we’d be hiking through. Larry had us at “Greenland,” an island three times the size of Texas, 80 percent of which is covered by an ice sheet that’s between 400,000 and 1 million years old and almost two miles thick.

The trail starts near the western edge of the ice cap and continues across one of the island’s largest snow-and-ice-free expanses to Sisimiut and the Davis Strait, which separates the Labrador Sea and Baffin Bay.

Within a day or two of agreeing to go, I started researching the trail and found images of rolling, domed mountains; open, craggy valleys; and Caribbean-blue lakes ringed with blooms of purplish willowherb, the national flower of Greenland. It was a mash-up of landscapes from “Game of Thrones” and “Lord of the Rings,” only without the anthropomorphic Ents — or any trees, really, since Greenland is so far north.

Because I had never before done such a long backpacking trip — in terms of mileage or nights out — and because I’m a compulsive list-maker, at this time I also started one in my journal: “Things We Might Encounter When Hiking for Nine Days in the Middle of Nowhere in Greenland.” As imaginative as many of the entries on this list were — a rabid musk ox or reindeer, or an August blizzard — wildfires never made the list.

A week before we left for Greenland, with concerned family and friends emailing us links to wildfire articles, Derek called the Sisimiut fire chief and got a more detailed description of the fire while Larry connected with an Arctic Circle Trail group on Facebook. We learned the trail was smack in the middle of the fire zone, but that hikers had been safely walking through it.

Sisimiut, the second largest city in Greenland, combats gloomy maritime weather with bright colors. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

Sisimiut, the second largest city in Greenland, combats gloomy maritime weather with bright colors. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

[***]

It was under clear, blue skies — no smoke or haze in sight or smell — that we set out from Kangerlussuaq, about 40 miles from the wildfire and home to about 500 people and Greenland’s biggest airport, to start the trail. Each of us carried all of the supplies and food we needed for the next nine days. (Hikers usually spend between seven and 12 days on the trail; we had devised a nine-day itinerary.)

My research missed the fact that the “trail” from Kangerlussuaq itself is 10.5 miles of gravel road until it reaches the trail proper. Before three miles passed, I vowed that if I ever did this hike again, I’d pay Kangerlussuaq’s sole taxi, a Creamsicle-colored compact car that had already passed us three times, whatever its driver charged for a ride to the start of the actual trail.

Shortly after we hiked past a 105-foot-diameter radar antenna at the Sondrestrom Upper Atmospheric Research Facility, all signs of civilization disappeared. Almost. A couple hundred yards in front of us, someone had painted a half-moon on the side of a boulder, in bright red, next to a well-worn dirt track lined with cottongrass. Finally, the Arctic Circle Trail!

Like many long-distance treks, the trail has markers along its entire length. These are often at the top of a pile of rocks, called cairns, formed by hikers to be visible from a distance. The trail’s red half-moon markers are a nod to Greenland’s flag.

It wasn’t far past the first half-moon that we found ourselves walking along the shore of a lake I thought I recognized from my research. We were too late in the season for the willowherb along its shores to be in bloom, but I didn’t care because the water was bluer than Paul Newman’s eyes.

[***]

My research never revealed a definitive history of the Arctic Circle Trail. From the same Facebook group that gave Larry more details about the fire, I learned that in the early 1990s, Sisimiut resident Johanne Bech — now 65 and still hiking the trail — was one of a small group of people tasked with erecting the first cairns. In 2010, Cicerone published Paddy Dillon’s “Trekking in Greenland: The Arctic Circle Trail.” At that time, about 300 people hiked the trail every summer. Last summer, when I did it, so did about 1,600 other hikers.

Long before hikers discovered the trail, though, the local Inuit (or Kalaallit in the Greenlandic language) used the route in winter, traveling along it on sledges pulled by dogs or snowmobiles. This past June, more than 1,500 square miles of land in this area, including about half of the trail, was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site for its “rich and well-preserved material and intangible cultural heritage.” The Aasivissuit — Nipisat Inuit Hunting Ground bears evidence of 4,200 years of human history.

The Hundeso Hunting Cabin, the first of the nine huts along the trail, is just south of the new World Heritage site. We spent our first night there. Hundeso is not a hut so much as a collection of campers haphazardly sewn together, onto the side of which a wood deck of indeterminate structural integrity has been built. It had a certain wild charm to it, and its bunks were unoccupied, but I was glad we had a tent with us.

We pitched our tent on a 100-yard-wide grassy strip of land between two lakes with surfaces as smooth as the sealskin I saw stretching on the side of a house in Kangerlussuaq. Because the magic sunset hour is about five hours long in Greenland in early-to-mid August (and sunset doesn’t happen until 10 p.m.), while Derek and Larry cook and eat dinner, I stalk the shores of both lakes with my camera.

[***]

Our days developed a rhythm. We tried to sleep as long as possible after sunrise, which happens at about 2:30 a.m. (This was easier for me than for Derek or Larry, because I brought an eye mask.) When the sun got too bright and the symphony of birds — Greenland wheatears, Lapland longspurs and Greenland white-fronted geese, among others — became too loud to ignore, we emerged from our tent onto the shore of a lake that was every bit as glowy in the morning light as it was at sunset. There were no other campers in sight. The lake’s far shore may or may not have been a giant, gently sloping slab of gray-pink granite. We made breakfast, broke down and packed up the tent, sterilized water to drink and, finally, switched from camp slippers (mine are Crocs) to hiking shoes and shouldered our packs, which weighed about 40 pounds each. Then we started walking into a landscape that kept us in a constant state of awe with its awesomeness, scale and emptiness.

We spent the entirety of one day walking along the shore of one lake. On another day, we spent hours gradually climbing to the top of a valley only to reach a saddle that drops down into an improbably longer and broader valley; gawping at this new terrain, there wasn’t a single man-made structure we could see that wasn’t a cairn.

Last summer's wildfires along the Arctic Circle Trail are believed to have been started by a campfire or cigarette. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

Last summer's wildfires along the Arctic Circle Trail are believed to have been started by a campfire or cigarette. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

Because there was so much daylight, we were never in a hurry. We took frequent breaks for water and snacks; sometimes, we even took off our shoes and socks, and soaked our feet in a lake or creek. On other treks, I’ve often raced the sunset: Must set up camp and cook dinner before the sun sets! On the Arctic Circle Trail in August, we could set up camp at 9 p.m. and still have plenty of daylight.

[***]

Our third morning started by hiking past the second hut, Katiffik. At the eastern end of Lake Amitsorsuaq, the hut was painted red and white on the outside and was bright and clean inside. (A note tacked onto one wall read: “YOUR MOM IS NOT HERE! So pick up your trash and take it with you — all the way.”) Two hearts are carved into the sign above the hut’s entrance. We took a snack break alongside a German father and son.

Katiffik was within about 12 miles (as the crow flies) of the wildfire we had read all about. Still, as we sat outside it munching on salami and cheese, there was no sign of fire — no acrid smell in the air, no haze on the horizon. It stayed that way all day. Seeing a reindeer nonchalantly munching on berries and grass and a ptarmigan comfortably nestled in a patch of crowberry bushes led me to think the fire was no longer an issue.

There was still no sign of the fire until we set up the night’s camp and started to fix dinner. As my dehydrated bacon and eggs rehydrated and Larry and Derek’s pasta cooked, the wind picked up. By the time our food was ready, there was so much smoke and haze we could no longer see more than a mile up the lake. We had no fear that the fire would reach us overnight — the Sisimiut fire chief told Derek it was a peat fire, and these are slow-burning — but we still decided to move our camp three miles back down the lake to get away from the smoke.

Hikers have decorated many of the cairns — piles of rocks made to be visible from a distance — marking the trail. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

Hikers have decorated many of the cairns — piles of rocks made to be visible from a distance — marking the trail. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

At our new camp, rays from the setting sun were the colors of a three-day-old bruise and ominously stretched out like a welcome mat for the horsemen of the Apocalypse, but the air no longer smelled of smoke. We went to bed hoping the wind would die down overnight and, combined with cooler overnight temperatures, would dampen the smoldering and smoke.

That’s exactly what happened. We made it within about a mile of the fire before we saw any evidence — just smoking ground — of it again.

The closer we got to it, the more appropriate I felt my initial description of the trail’s landscape was. Here, it looked like the aftermath of an epic battle between “Game of Thrones” dragons and “Lord of the Rings” Orcs. Since the start of our hike, the days had been in the 70s — the hottest (and driest) summer on record in Greenland. I was ready to tie a wet T-shirt around my face to protect myself from inhaling smoke, but I had been in smokier bars and clubs. Still, the scene was dramatic.

That night, we named our camp “Mediterranean Beach,” because that’s what it looked and felt like — except there were no crowds, and it was on the Arctic Circle.

Like wildfires, lake swimming — and anything related to hot weather — was absent from my list of things we might experience in Greenland. But the way-above-average temperatures, combined with few clouds in the sky and the lack of shade trees along the trail, often made me feel like I was being roasted. So most days, I cooled off in a lake.

After beach camping, the author encountered something that was not on her list of “Things We Might Encounter When Hiking for Nine Days in the Middle of Nowhere in Greenland” — sunburn. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

After beach camping, the author encountered something that was not on her list of “Things We Might Encounter When Hiking for Nine Days in the Middle of Nowhere in Greenland” — sunburn. (Dina Mishev/For The Washington Post)

Two nights later, we found “Reindeer Beach” — a campsite we so named because there are no human footprints but dozens of reindeer tracks on it. Here, Derek and I did a pre-dinner full submersion. The conditions — temperature, latitude — were such that I was able to comfortably sunbathe long enough to accidentally get a mild sunburn.

The next evening was cool enough to finally wear one of the two pairs of pants I’d been carrying since Kangerlussuaq. The morning after that, there was a misty rain. Because this was the weather I’d expected to be hiking in the whole time (and because my single pair of shorts stank and were stiff with salt despite my daily rinsings) I was prepared: I happily mined some Gore-Tex rain gear from the depths of my pack.

I was even better prepared for the next day, our last on the trail. We woke up to the sound of driving rain and unzipped the tent to find that we were in a cloud and that there was snow on a hillside not far above us. It wasn’t rain lashing our tent, but sleet — an August blizzard! — straight from my “Things We Might Encounter When Hiking for Nine Days in the Middle of Nowhere in Greenland” list.

For the final miles to Sisimiut, despite the weather, I was completely comfortable: I wore both pairs of my hiking pants, a hat, gloves and my Gore-Tex armor. I had only one problem: My rain jacket really chafed my sunburned shoulders.

Four days later, our Air Greenland flight from Sisimiut back to Kangerlussuaq almost exactly tracked the trail. Lake Amitsorsuaq is easy to pick out. There was no smoke — or even any smoldering — to be seen.

Mishev is a writer based in Jackson Hole, Wyo. Find her on Instagram: @dinamishev.

by Dina Mishev

This article first appeared on /www.washingtonpost.com. The original can be read here.