Trekking News

6 years, Australia

Yosemite Just Got a Quad-busting 94-mile Hiking Route

It’s hard to imagine there would be anything new to find in a place as well loved as the 128-year-old Yosemite National Park. But professional backpacker Andrew Skurka scoured maps and set out on a scouting trip in August along the Sierra Crest in search of a new route through one of the country’s most popular parks.

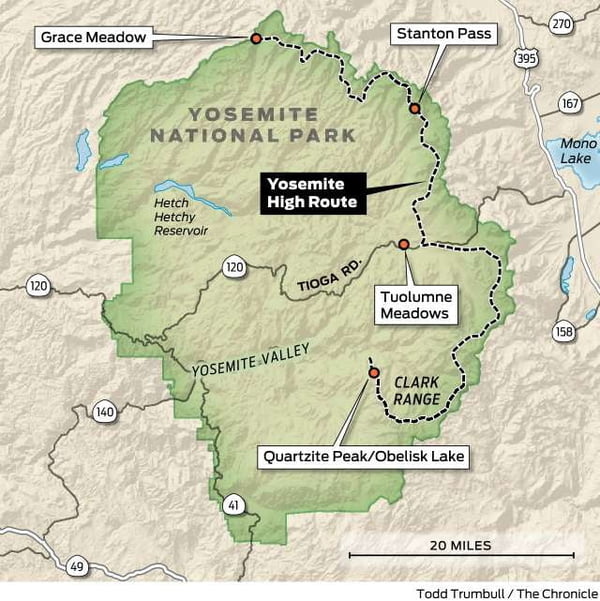

After nine days in the backcountry, the 38-year-old came away with a pick-your-own-adventure trek. At its core, the route is 94 miles long and runs from Grace Meadow in the north to Quartzite Peak in the south. Skurka calls it the Yosemite High Route.

Backpackers hiking in Yosemite's remote wilderness. Photo: Courtesy Andrew Skurka

Backpackers hiking in Yosemite's remote wilderness. Photo: Courtesy Andrew Skurka

“Its scenery and off-trail travel make for a consistent world-class backpacking experience,” Skurka says. “Its terrain is physically challenging but never contrived or stupidly hard.”

A high route is an off-trail path that typically contours around deep valleys and climbs over steep passes in high-elevation regions. Attempting a high route is like mixing mountaineering and backpacking. Ropes aren’t necessary on Skurka’s route, but there are a few exposed Class III scrambles up and down steep rocky passes where a slip and fall could result in a broken leg or a busted head.

With the northern and southern termini of the Yosemite High Route buried deep in the backcountry, hikers can pick from a dozen approach trails of varying distance to access the main route, and various loop options can extend the route up to 162 miles. Tuolumne Meadows, along Tioga Road, serves as a central point of access; the route stems both north and south, and trail offshoots loop back to the meadows at its center.

The route takes hikers off trail through some of the most remote parts of the park, across sections of moraine and up steep talus passes. It stays above forested valleys and presents hikers with spectacular vistas at every turn. In total, the core 94 miles covers more than 28,000 vertical feet of elevation gain.

“I’m by no means the first person to have linked things together. I guarantee, people who’ve been Yosemite aficionados for 30 years have done large sections of this route,” Skurka says.

Skurka lives in Boulder, Colo., and rose to prominence in the outdoor world in the mid-aughts when he developed long-distance trails. One of them is the 6,875-mile Great Western Loop, a monster route that links together the Pacific Crest Trail and the Continental Divide Trail. He has logged tens of thousands of miles in the wilds of the U.S. and Canada and been named “Adventurer of the Year” by both National Geographic and Outside magazine.

In 2008, Skurka hiked the Sierra High Route, a 195-mile off-trail route along the Sierra Crest that parallels the John Muir Trail, and recognized the endless potential in ditching the trail, losing the crowds and orienteering between landmarks.

“That was an eye-opening experience, because up until that point I had just been following trails — a lot of trails,” Skurka says. “I was like, ‘Oh, wow, you can do a long hike, but make it way more adventurous.’ You have to be much more present, it’s more physically rigorous, and you have to have a high skill level.”

In March, Skurka published a guide to the Yosemite High Route — his fourth. It includes a written guide, datasheets listing waypoints, maps and GPX files to upload to mobile devices. (It can be purchased for $25 on his website, AndrewSkurka.com.) Like the rest, it’s largely a labor of love. The 120-plus hours he spent compiling his adventure into directions for a small niche of hard-core backpackers isn’t the “most efficient use of time,” he says. (Guiding trips and reviewing outdoor products are his main sources of income, he says.)

“Seeking out these routes is personally fulfilling — backcountry adventures are challenging and engaging,” Skurka says. “There’s also an element of giving back and sharing highlights of my summers. I get a lot of feedback from people who’ve used these guides to explore places they wouldn’t have otherwise.”

The northern section of the Yosemite High Route parallels part of the Sierra High Route and descends the notoriously scary Class III scramble on the north face of Stanton Pass. In the northern loop, backpackers also travel through the remote and largely trailless canyons south of the Pacific Crest Trail in Jack Main Canyon.

Backpacker Andrew Skurka in Yosemite National Park. Photo: Courtesy Andrew Skurka

Backpacker Andrew Skurka in Yosemite National Park. Photo: Courtesy Andrew Skurka

On the south end of the route, backpackers will find themselves in the rarely traversed Clark Range, and will travel through Clark Canyon, up Quartzite Peak — which Skurka calls a “five-star view” — and down toward the scantily visited Obelisk Lake. In the process, hikers trek over talus passes, granite slabs and sections of loose scree.

Skurka warns the route isn’t recognized by park officials and will likely be unknown to rangers. But to do it you’ll need to apply for wilderness permits online. The permits are issued through a lottery system 24 weeks before any given date and are based on the starting trailhead.

“For thru-hikers, high routes force them to take their skills to the next level,” Skurka says. “They can pack adventure and challenge into a long weekend.”

by Nick Rahaim, freelance writer in the Monterey area. Email: travel@sfchronicle.com

This article first appeared on http://www.sfchronicle.com. The original can be read here.