Trekking News

6 years, Australia

A Glimpse of Berber Life – Trekking in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains

A short drive from Marrakech lies a heavenly retreat, stunning views and . . . tough climbs

The heart of a walnut is a delicious, nutritious and surprisingly beauteous thing. Such are my musings on a trekking tour of the High Atlas Mountains where, in the midday heat, I value the shade of the walnut trees on the arid red sandstone slopes.

This inner beauty within a hard shell is a feature of Morocco: the Tardis-like riads of Marrakech that open into colourful lodgings; the centuries of artistry hidden behind the hard-core haggling of the souks; and here, in the High Atlas Mountains, the inner beauty and innate benevolence of the Berber people. Or the Amazigh, meaning “free people” as they prefer to be known.

Catherine Mack enjoys the view after an arduous climb

Catherine Mack enjoys the view after an arduous climb

Mike McHugo has known all about these Berber qualities since the 1970s, when he first came trekking here. An adventurous traveller from England, his mountain guide back then was a Berber, Omar Ait Barmed, with whom he became good friends and went on to restore a ruined kasbah 20 years later.

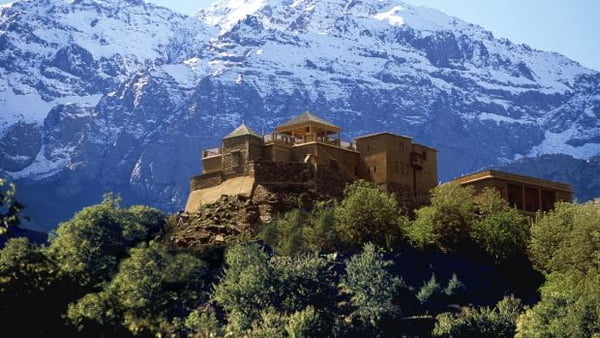

The Kasbah du Toubkal is now a majestic beauty in the heart of the High Atlas Mountains and my trekking base for the next few days. I have had a photograph of it as my desktop image for years now, shouting at me on a daily basis to get my itchy travel feet into hiking boots and up into the Atlas.

Just an hour-and-a-half from Marrakech airport, I am transferred to the kasbah by one of their drivers who drops me in Imlil village. Buzzing with adventurer types, Imlil is gateway for trekkers aiming not just for the high Atlas trails but for the great summit itself: Jebel Toubkal, the highest peak in north Africa at 4,167m (13,671ft).

The kasbah is inaccessible by car, but just 15 minutes’ walk from the village centre, so my bag is handed over to a man with a mule who places it on the saddle and guides me up through walnut groves, interspersed with rug and tagine sellers, to a great wooden door; made of walnut of course. Inside, a secret world of flower-filled gardens, a steaming hammam and traditional stone buildings.

A walking pole in a vital piece of kit in this rugged terrain

A walking pole in a vital piece of kit in this rugged terrain

The kasbah’s mission since day one has been to create a Berber hospitality centre, not an exclusive mountain resort, a road they could have easily gone down. In fact, it was originally created to host student trekking groups but, when electricity arrived in Imlil in 1997, they were able to invite a wider array of guests. But equality is still at the heart of the kasbah, with student groups hosted in dormitory rooms juxtaposed with higher-income travellers in private en suite rooms with priceless views.

The kasbah also respects the traditions of its surrounding Imlil Valley Berber communities. The staff are all Berber, one of whom greets you with a silver water pot to rinse your hands with rose water; there is no alcohol although you are welcome to bring your own. The superb food is traditionally Berber and instead of white bath robes in your bathroom you have traditional djellabas and leather Berber slippers.

Last but not least, there is a 5 per cent levy on all bookings, which goes towards the important Bassins d’Imlil organisation, funding projects within the Imlil Valley communities. These include buying a local ambulance to funding boarding houses for Berber girls from remote communities, so that they can attend secondary school, in a brilliant initiative called Education for All (efamorocco.org)

The real insight into Berber culture takes place over the next two days when I take on my 21.5km trek, beginning straight out of the kasbah’s front door. I have two Berber companions, my guide Mohamed Ahroche and a 17-year-old muleteer, Youssef. I had been concerned that there might be some male-female divide or, even worse, an embarrassing kowtowing towards the tourist. But these boyos are bursting with banter and have me in stitches from the get go. There is clearly no divide in the mountains, only shared wisdom, love of landscape, humour and, surprisingly, song.

On one quite tough ascent to Tizi h Mzik (2,489m) I start to feel queasy. The lads suggest I let the mule carry me for the rest of the morning as my queasiness isn’t abating, but I am determined to complete the ascent. As we continue Mohamed starts to sing gently in Tamazight, the Berber language, while Youssef repeats each sung phrase in a sort of gentle meditative chant which echoes across the valley. Being enveloped by beautiful mountains and melodies gets me through my nauseous blip, Mohamed reaching out his hand to help me on the climb up through the last few metres.

There’s no shortage of food on this trekking trip, with a cooked lunch waiting for us at some gorgeous viewpoint, the cooks having gone up earlier, their mules carrying tagines, teapots and copious treats to top us up for the afternoon walk. Today’s panoramic picnic is across the magnificent Imlil Valley which we have just climbed, as well as the white peak of Adra el Hajj (3,140m).

I feel right as rain again for the second part of my trek, along gently ascending and descending rocky paths, the land turning from red to green as we approach the cultivated terraces of Tizi Oussem, a traditional Berber Village with a few flat roofed, mud and stone houses built into the mountainside. Here, cherry, apple and walnut trees abound and men on donkeys transport boxes of fruit to and from the local market. The view is sweet too, overlooking the Azzaden Valley and Ait Aissa Village which is home to the kasbah’s own trekking lodge, where we are spending the night.

As we descend towards the lodge, Berber women dressed in magnificent colours stroll past us, gossiping and grinning. Mohamed tells me they are all en route to a local wedding, which are big community events in the Atlas. He then shares that he too is getting married in two weeks’ time and they are preparing to have hundreds of guests from the six Imlil Valley villages. “If you can come back that weekend, you are more than welcome,” he says with his usual sincerity and smile. I wish.

The trekking lodge proffers the same Berber warmth that I have now come to expect: the rosewater hand washing ritual, a revitalising hammam, Berber rugs and cushions on the balcony overlooking the roofs of other houses, where everything from fruit to colourful Berber clothes are spread out to dry in the baking sun. My cosy bedroom window looks straight up at Tizi n Ouanoukrim, with two summits which are the second highest in the Atlas range.

Kasbah du Toubkal. Photograph: Alan Keohane

Kasbah du Toubkal. Photograph: Alan Keohane

Over dinner I leaf through the guest book, dating back to 2006, and the same words keep jumping out about this heavenly retreat: serenity, majesty, special, kindness and welcome. Looking out at the full moon which illuminates the mountains and valleys all around, I feel as if I could find a similar adoring adjective to for every star I could see. Which is a lot.

Our second day of trekking starts with the most stunning ascent up to Tizi Oudite (2,219m) with views across the Matate Valley. The sun still shining, I remove my early morning layers one by one and let the Atlas’s blue skies inject me with a much needed fix of Vitamin D. From here we have a pretty tough descent through rocky terrain (walking poles are a must), meeting only a handful of goat herders en route.

Our second trekking lunch was by a bridge over the Ait Mizane river, where I bathe my feet in its cooling waters the source of which I can see right in front of me once again: Mount Toubkal, poised perfectly at the top of the valley. The final trek of the afternoon brings us back through some ancient walnut groves which line the river, through several more traditional Berber villages, past a couple of waterfalls, and finally back to the kasbah. We are welcomed back like family members, the fires in the hammam all stoked and good to go.

Going back through security at Marrakech airport, just over an hour away, is a definite jolt back to reality and one I am not feeling quite ready for, having been absorbed by mountain magic. Forgetting to take my belt off going through security, the beeps go off and I have to be searched.

“Can you show me what’s in your pocket please?” asks the security woman, feeling some odd shaped item in my fleece pocket. I put in my hand in and pull out a walnut, which Mohamed had picked up for me on the mountain just the day before. “Oh that’s fine,” she says. “You can go on through”, oblivious to everything this hard shell now represents for me.

It sits on my desk as I write, forever a reminder to step out of my protective shell as often as I can. Because, in the words of Ibn Battouta, a 14th century Amazigh explorer: “Travelling – it leaves you speechless, and then turns you into a storyteller.”

by Catherine Mack

This article first appeared on http://www.irishtimes.com. The original can be read here.