Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

95 Years Ago, Everest Was Just as Deadly but Much Less Crowded

As climbers continue to die in the Himalayas, a look back at the conquest of the tallest mountain in the world.

The mountains are deceptively calm. Snow-covered, sometimes they blaze bright enough to blind. They appear indifferent to the tiny travelers on their backs — these European men in the waning years of the British Empire, seeking, as the stories of the time often read, to conquer Everest.

Capt. John Noel was a photographer and filmmaker who accompanied the Royal Geographical Society’s 1922 expedition up Mount Everest — the first documented attempt to summit the highest peak on earth. Using a telephoto lens, he captured George Finch and Capt. John Geoffrey Bruce’s progress in a short film, “Climbing Mt. Everest,” the first motion picture made at that high an altitude. Circa spring 1922.Credit: The New York Times

Capt. John Noel was a photographer and filmmaker who accompanied the Royal Geographical Society’s 1922 expedition up Mount Everest — the first documented attempt to summit the highest peak on earth. Using a telephoto lens, he captured George Finch and Capt. John Geoffrey Bruce’s progress in a short film, “Climbing Mt. Everest,” the first motion picture made at that high an altitude. Circa spring 1922.Credit: The New York Times

Conquer? Really? Who conquers whom? If you’ve ever faced the Himalayas, you know they can swallow you whole.

These are some of the earliest pictures of the highest peak on Earth, taken on British expeditions in 1921, 1922 and 1924. They are among the first pictures of our species trying to scale it — and to document the feat for future generations.

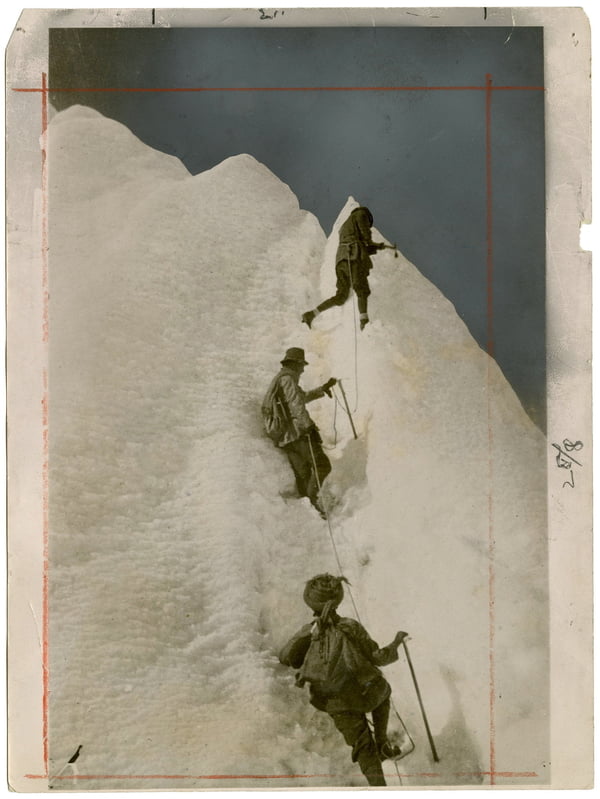

Mount Everest was, and still is, the holy grail for mountain climbers. Members of the 1922 expedition used ice picks to hack footholds into a pristine slope, 23,000 feet up the Himalayan peak. Ropes, aluminum ladders and other climbing aids are now affixed to many spots along the route to the summit. Circa spring 1922.Credit: The New York Times

Mount Everest was, and still is, the holy grail for mountain climbers. Members of the 1922 expedition used ice picks to hack footholds into a pristine slope, 23,000 feet up the Himalayan peak. Ropes, aluminum ladders and other climbing aids are now affixed to many spots along the route to the summit. Circa spring 1922.Credit: The New York Times

Look at those tiny creatures — that’s us! — walking in a row against the dazzling white wall of ice. See, they are hacking at the mountain to dig steps in which to place their feet. By 1922, a British expedition team got within hundreds of feet of the summit.

What these pictures don’t fully tell you is that the mountains are not calm at all. They growl when stones tumble. The wind whistles as you climb. The altitude drains your breath. They tell you how puny you are, how frail really, which is why you try to supplicate them, as the Buddhists who are from those mountains do, by stacking one stone on top of another in prayer.

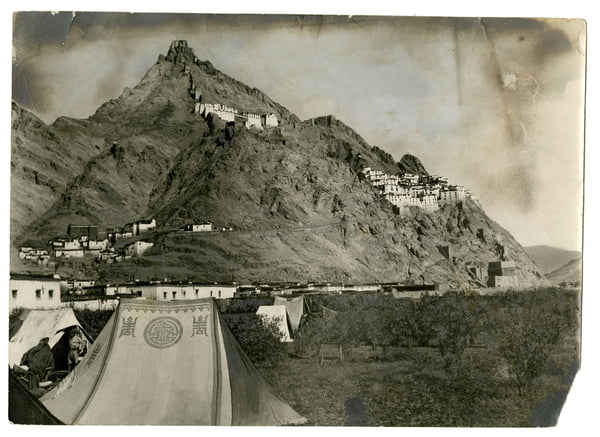

During the 1921 reconnaissance expedition, the group camped near the town of Shekar Dzong. At the time, Nepal was closed to foreigners, so any approach to Everest had to be made from the Tibetan side. Credit: The New York Times

During the 1921 reconnaissance expedition, the group camped near the town of Shekar Dzong. At the time, Nepal was closed to foreigners, so any approach to Everest had to be made from the Tibetan side. Credit: The New York Times

Everest, the peak, is named after a bureaucrat of the British Empire, a choice that itself foregrounds man over nature. The people of the Himalayas often refer to it as a goddess or a mother. In the pictures, they peek out from between the white men’s shoulders. In the captions, they are often unnamed, referred to as “sturdy native porters.” Their humanity had already apparently been conquered.

The pictures are a glimpse into our collective capacity for adventure and courage. But looking at them now, they are also a glimpse into our capacity for self-destruction, our ability to squander what we love.

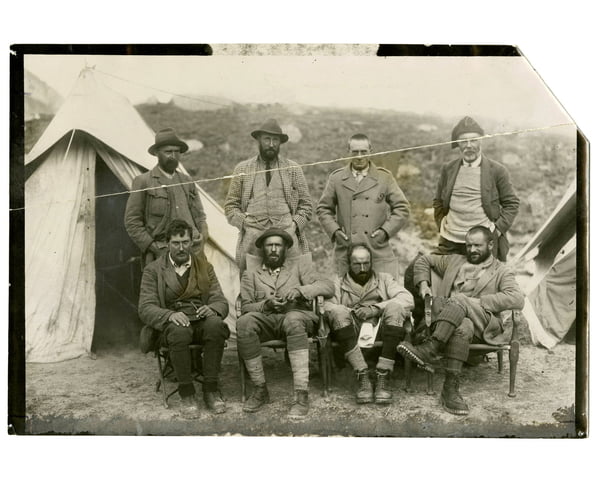

Members of the 1921 reconnaissance expedition, which laid the groundwork for the 1922 summit attempt. Standing from left are Dr. Sandy Wollaston, a physician and naturalist; Colonel Howard-Bury; Dr. Alexander Heron, a geologist; and Harold Raeburn, a mountaineer. Seated from left are George Mallory, a climbing expert; Capt. Edward Wheeler, a photographic surveyor; Guy Bullock, another climber; and Maj. Henry Morshead, a surveyor. Credit: The New York Times

Members of the 1921 reconnaissance expedition, which laid the groundwork for the 1922 summit attempt. Standing from left are Dr. Sandy Wollaston, a physician and naturalist; Colonel Howard-Bury; Dr. Alexander Heron, a geologist; and Harold Raeburn, a mountaineer. Seated from left are George Mallory, a climbing expert; Capt. Edward Wheeler, a photographic surveyor; Guy Bullock, another climber; and Maj. Henry Morshead, a surveyor. Credit: The New York Times

What we know now is that by the time of these expeditions — as industrialism was enthusiastically conquering nature — we were already beginning to alter the Himalayas forever. The powerfulamong us, in Europe and the United States mainly, enlarged our economies as fast as we could by burning as much fossil fuel as we could.

The greenhouse gases we injected into the atmosphere have already warmed the planet measurably. They continue to, at an accelerating rate. As a result, the ice is melting in the Himalayas. At the current pace, scientists forecast that at least a third of the ice in the Himalayas and the neighboring Hindu Kush range will thaw by the end of this century.

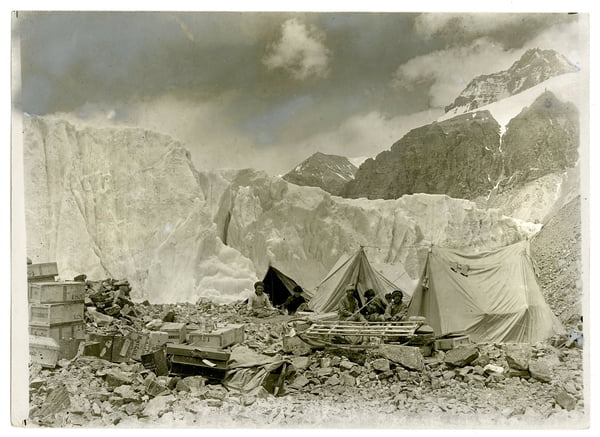

The crew made three attempts to reach the summit of Mount Everest in the spring of 1922. After the third try — during which an avalanche killed seven porters — the team gave up and returned to its Rongbuk Glacier camp. Credit: The New York Times

The crew made three attempts to reach the summit of Mount Everest in the spring of 1922. After the third try — during which an avalanche killed seven porters — the team gave up and returned to its Rongbuk Glacier camp. Credit: The New York Times

Why should that matter? These mountains are the water towers of Asia. When the ice is gone, the water is gone too, affecting more than a billion people who live downstream. Then there is nothing left to conquer. No ascent of man.

The mountain is indifferent, as nature almost always is to those of us who think we are somehow something other than just a part ofnature.

Pictures are meant to be the repository of our collective memory. The Himalayas hold our memories too. As the ice thaws, it releases the bodies they swallowed long ago.

This article first appeared on http://www.nytimes.com. The original can be read here.