Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

Jan Morris - Surviving Member of the 1953 Everest Expedition

Everyone here seems to know Jan Morris, even the waitress at the local fish restaurant. “Have you met Jan before?” she asks as Morris materializes from what, due to a trick of the light, looks to be the ocean itself, clouds of white hair wafting and fluffing around her face.

Tom Jamieson for The New York Times

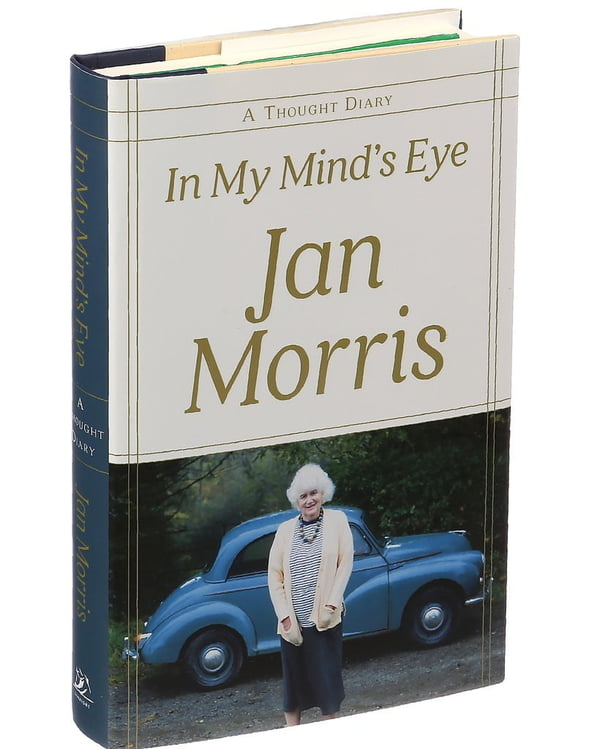

Morris is 92 and walks carefully, with the help of a cane. She has lived in this corner of North Wales — a 3-plus hour train ride from London, and then another 45 minutes by car — for most of her life. In Britain, she is a renowned and beloved essayist, historian, journalist and chronicler of places, the author of more than four dozen books, but it wasn’t until her latest work, “In My Mind’s Eye,” was serialized on BBC radio last fall that many of her neighbors realized there was a celebrity in their midst.

Morris has lived many lives, and it is impossible to separate who she is now from who she was before: James Humphrey Morris, who was born in 1926 in Somerset, England, and whose education and career were typical of privileged Englishmen at the time.

Morris was a choral scholar at Christ Church, Oxford; served in the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers during the waning years of World War II; and at age 23, met and married Elizabeth Tuckniss, the daughter of a tea planter. They raised four children together (a fifth died in infancy).

Morris worked as a journalist specializing in splashy, intrepid assignments for the Times of London. In 1953, the exclusive account of Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s historic ascent of Mount Everest turned Morris into that rare thing, a famous journalist, because of how exciting and competitive the story was and how physically dangerous to cover.

“I Had Been Born Into the Wrong Body”

A different sort of fame would come in 1972 when, after a lifetime of feeling trapped inside a body that felt as if it belonged to someone else, Morris traveled to Casablanca and underwent gender-reassignment surgery. She was 46. It was an extraordinarily bold thing to do. Few people at the time understood what such a transition entailed, let alone knew anyone who had one.

“I was 3 or perhaps 4 years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl,” the author, now known as Jan, wrote later in “Conundrum,” her account of her struggle to reconcile body and spirit.

Sonny Figueroa/The New York Times

Sonny Figueroa/The New York Times

Freed from the constraints of her old body, and freed perhaps of the expectations that come with being a male writer, Morris shifted into a different sort of writing, writing lyrical non-fiction books about places (Venice, Trieste and Oxford, among others) and history, including “Pax Britannica,” a three-volume history of the British Empire.

The biggest constant in her life has been Elizabeth, who was first her wife and then her ex-wife — same-sex marriage was illegal in Britain in 1972 — and is now her legal civil partner, her closest companion for more than 70 years. The couple settled here in Wales; Elizabeth mostly stayed home and Morris lived a peripatetic existence, traveling and writing and then traveling again.

17,900 Feet to Base Camp

At lunch, wrestling with a pizza and sipping a glass of wine, Morris is looking back at her life from the vantage point of her 93rd year and reminiscing about the Everest expedition.

Covering the story required being embedded with the Everest team, climbing 17,900 feet to base camp for word from the summit, and then, thrillingly, sending a coded telegram via runner to announce the news to the world. Morris felt a kinship with the rest of the expedition, she said, that never really went away.

“It altered my life so much,” Morris says. “And now I’m the only surviving member of the expedition, and I miss them all.” When Hillary died, in Auckland, New Zealand, in 2008, the New Zealand government flew her and Elizabeth to mark the significance of their shared history.

Morris now lives in the difficult, vexing, preoccupying land of what she calls “extreme old age.” Although longevity has made her more interesting, she thinks, it is not so fun when there is too much of it. She is no longer able to travel much, for instance, and has had to curtail her old wanderlust. “Old age is a great mistake,” she says.

But the remark comes with such a disarming smile and so much charm. “In My Mind’s Eye” — a collection of mini-essays, written one per day over the course of many months — reveals that her writing is just as elegant and erudite, and her mind just as supple, playful, curious, rigorous, humorous and surprising as ever.

The essays range wildly, touching on, among other things, the superiority of her car; the beauty of Welsh rainbows; the felicity of the word “anathema”; the question of whether absolute truth in recollection is possible; the madness of contemporary politics; and the transcendent mundanity of family life.

As a journalist, Morris was embedded with Edmund Hillary's Everest team in 1953. "It altered my life so much. Now I'm the only surviving member of the expedition, and I miss them all," said Morris, pictured congratulating Hillary after the ascent. Credit: George Lowe/Royal Geographical Society, via Getty Images

As a journalist, Morris was embedded with Edmund Hillary's Everest team in 1953. "It altered my life so much. Now I'm the only surviving member of the expedition, and I miss them all," said Morris, pictured congratulating Hillary after the ascent. Credit: George Lowe/Royal Geographical Society, via Getty Images

She also writes about importance of kindness, to each other and to nature. When she sees a bug in the house, Morris ushers it to safety; when she inadvertently kills a woodlouse, as she recounts in a scene in the book, she apologizes.

“That’s the very last thing I wanted to do to an old friend,” she says to the dead woodlouse, as it disappears down the drain.

“It’s so simple, and everyone agrees with it,” she says at lunch, of being kind. “If you could make it the basis for all society, how lovely it would be.”

“To Me Gender Is Not Physical at All”

Morris is a handsome woman, tall and formidable, wearing a butter-yellow coat over a pair of trousers and sweater. She is impatient with questions about transgender politics, possibly because she made peace with her own decisions so long ago. Having reached her age and lived for equal amounts of time as a man and as a woman, she says, the transition she made so long ago somehow feels less relevant.

“I’ve never believed it to be quite as important as everyone made it out to be,” she said. “I believe in the soul and the spirit more than the body.”

Or, as she writes in “Conundrum”: “To me gender is not physical at all, but is altogether insubstantial. It is soul, perhaps, it is talent, it is taste, it is environment, it is how one feels, it is light and shade, it is inner music, it is a spring in one’s stem or an exchange of glances, it is more truly life and love than any combination of genitals, ovaries and hormones.”

In reading “Conundrum,” you’re struck (among other things) by the good humor, practicality and nonjudgmental nature of Morris’s friends and colleagues. Back then, most people seem to accept her transformation with equanimity, in some cases because they genuinely thought it was none of their business or were too British to bring it up.

Gender politics doesn’t seem to intrude too often around here, either, and Morris’s unconventional history has been at once extraordinary and perfectly normal to her neighbors, she says. “I’ve lived two genders, and in this part of Wales they haven’t twitched at all.”

Morris is happily working on another book of journal entries, though her age has given her the license to select only what she wants to do.

In “Mind’s Eye” she recounts her response when offered a writing assignment: “It’s very kind of you to think of me, but to be honest I can’t be bothered.” (To which the editor replied, “Bravo!”)

She also has another book of already-written essays, meant for posthumous publication.

“It’s quite a nice book, but I don’t know why I have decided that this particular one shall be my last,” she says. “Everyone thinks it’s because I have a flaming revelation. I wish I had, but I haven’t.”

“That Subtle Demon of Our Time”

Morris’s deep love of Elizabeth, her lifelong companion, has run like a golden thread through the conversation. When they first met, they so delighted in each other’s company that when Elizabeth took the bus to work, Morris would ride with her so the two could keep talking.

Tom Jamieson for The New York Times

Tom Jamieson for The New York Times

But now Elizabeth is suffering from dementia, what Morris calls “that subtle demon of our time,” and it is a difficult time for a couple who have always shared everything. Morris prefers not to dwell on it, but it is clear that weighs heavily.

It has made both of them by turns bewildered and grumpy and scared, she says. But “kindness reconciles us still,” Morris writes in “Mind’s Eye.” “In all our long years together, in life as in love, we have not once said good night without the sweet kiss of reconciliation.”

They have already had a headstone made for the grave they will eventually share. It is sitting under the stairs in their house.

It says, in both Welsh and English: “Here are two friends, at the end of one life.”

by Sarah Lyall

This article first appeared on http://www.nytimes.com. The original can be read here.