Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

Meet the world’s only professional sea stack climber

To reach the top of a sea stack you must overcome ferocious seas and towering rock walls – it’s no wonder Iain Miller is one of the few people to do it.

Iain Miller is a full-time professional sea stack climber who spends his days guiding visitors from all over the world up and down the giant rock towers that line the waters off Ireland’s rugged Donegal coast.

And the insanity of his day job isn't lost on him.

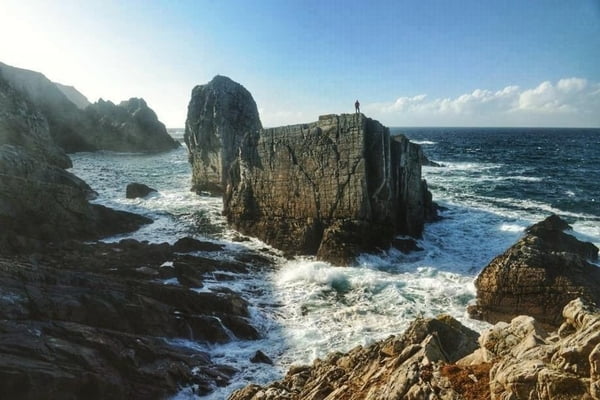

Surrounded by the forces of nature © IAIN MILLER

Surrounded by the forces of nature © IAIN MILLER

“It was 6am and I was on a small rocky outcrop at the base of a 250m sea cliff, nearly 30km from the nearest main road and totally and utterly alone,” he recalls. “In the far distance was the object of my desires, a mammoth sea stack, but whistling winds were causing the sea to smoke and, in front of me, my little dinghy was writhing around in white water violence. All that was left to do was commit to a super-scary big leap into the rage and go for it….”

These pillars of rock, sliced off from the cliffs by coastal erosion, are found all around the world, but very few people have the unique combination of climbing and nautical skills required to reach their summits.

Miller has topped out on more than 50 – so he's the perfect man to ask what it’s all about.

How did you start climbing sea stacks?

I was living in the Orkney Islands in Scotland and started using my sea skills to find ways to approach their famous sea stacks.

The first one I climbed was The Clett of Crura in the Orkney Islands in 1999. It was a roped solo, the second-ever ascent of the stack, and it was a bit reckless, as I didn’t know how I would get off the summit. The tide was high and at the time I knew very little about this type of adventure. I soon saw the challenge of getting to sea stacks offered extra excitement over rock or sea cliff climbing and also realised few climbers were doing it.

What's so special about sea stack climbing?

Most sea stacks have had fewer people on their summits than have stood on the moon – so it’s the unknown element of the experience that keeps luring me to these nautical summits.

Standing on top of Dun Briste sea stack © IAIN MILLER

Standing on top of Dun Briste sea stack © IAIN MILLER

I’m not sure who said it first but my mantra has always been ‘an adventure is simply a journey in which the outcome or destination are uncertain.’ It’s all about venturing to a place nobody has ever been to, one that requires a huge amount of planning and the right weather conditions to get there.

What sea skills do you need to have to do this, then?

You need to respect the sea and understand how it interacts with exposed and submerged stationary objects. I am perhaps the polar opposite of a surfer looking for the peak waves – I watch the sea to find channels of calm created by seawater moving around rocks, islands, sea stacks and skerries.

I use the knowledge I've built up over the years to predict the safest passage to and from the stack by spotting the safe routes that allow me to transit quite rough seas, following the black channels that exist on the leeward side of all stationary fixed objects.

The return trip is often more challenging because predicting what the sea will be doing in several hours time – the time it takes to climb the stack – takes a lifetime to master.

So how do you usually get to a sea stack?

I use a small dinghy that I can carry on my own. It has three separate inflatable sections, so it can stay afloat on only one active chamber and it won’t sink even if it’s filled with water. It also has a sturdy grab rail and room for two people and dry-bag cargo.

How you get there is dictated by the length of sea passage. When the stack is less than 60m from land, it's sometimes possible to use the dinghy to rig a Tyrolean traverse, but that's limited to easier, more accessible stacks.

On the top of the Sturrall sea stack © IAIN MILLER

On the top of the Sturrall sea stack © IAIN MILLER

Some stacks can be up to 2km from the nearest sea access point, often via a passage along the bases of 200m sea cliffs. That's when the commitment and ante are raised and you can’t just turn up on a sunny day and paddle out to the base. For those trips, I make at least one visit to the cliff tops to overlook the area and watch the interactions between the tides.

Once on the water, by carefully positioning the cargo and passenger and using a single paddle to steer, I can manoeuvre the boat in very narrow channels close to land.

And what does it feel like to complete a first ascent of a sea stack?

To arrive on the summit you'll probably have walked a long way over lonely cliff tops before descending a large cliff, often at least 200m high and covered in grass and scree, to arrive at an outstandingly beautiful storm beach in a remote and atmospheric location.

You'll have then crossed up to 2km of raging sea in an inescapable location to land at the base of a towering monster of rock then made it up several pitches of standard rock climbing, surrounded entirely by the forces of nature.

After all that, ending up standing on a pinpoint summit over 100m above the ocean, a pristine place far from anywhere, is actually quite a spiritual experience.

How many stacks have you done the first ascent of?

I have made the first ascents of over 50 sea stacks and climbed about 180 new routes on these stacks and previously climbed ones.

What are the three most amazing ones you've climbed and why?

Cnoc na Mara represents all that’s great about sea stack climbing – it’s remote, intimidating and in a surreal location in the shadow of Ireland's highest sea stack, Tormore Island. Free-soloing this a decade after making the first ascent was perhaps the most foolish thing I’ve ever done.

Dun Briste is a famous stack that has been seen by millions but only seven have stood on its summit. I made the second-ever ascent. It took me four attempts and it was pretty scary. Standing on the summit alone, in the rain, hyperventilating, I've never felt so detached.

Finally, Bothanvarra, in Donegal, is very big and very remote and I free-soloed it. I’m still the only person to have ever stood on its summit. I had a near miss on the approach in my dinghy so when I was climbing I had the illusion I’d drowned and was in a dream in the afterlife. I felt immortal, which in hindsight was a truly terrifying situation to be in!

And what sea stacks around the world would you love to climb?

It is my life’s ambition to stand on the summit of Balls Pyramid in the Pacific Ocean – ideally alone, but that's not perhaps a viable proposition. Risin og Kellingin in the Faroe Islands would be amazing, as would the Totem Pole and its larger but less technical neighbour the Candle in Tasmania.

I'd also love to climb Chaos Stack, Ireland's last unclimbed major sea stack. It’s in an extremely hostile location at the base of a 245m-high inaccessible sea cliff with a 2.5km sea passage the only viable access to it. I’ve made two attempts so far and the current results are Stack 2 Iain 0.

What is the scariest moment you’ve had while sea stack climbing?

I once fell about 18m into the sea and tumbled through a kelp forest under the water. Just as I was about to breathe out and drown I made it to the surface and saw a little girl standing by my boat at the base of the stack. My head bobbed down and when I looked again she was gone. I truly believe I glimpsed the afterlife then and she was some kind of angel.

You prefer to only climb solo – why's that?

I live in a mountain lodge in the centre of a blanket bog at the base of Errigal, Donegal's highest mountain, and I climb mostly on the west coast of Ireland, far from civilisation. As it’s rare to get good conditions and hard to plan in advance, soloing is often just a logistical necessity. It also allows you to face your greatest opponent, the inner you.

And you keep your climbs secret…

Yes, I firmly believe that if you solo you must be totally and utterly alone – and that means nobody knows where you are or what you're doing. It allows your mind to focus and truly be in the moment.

What's the key to success?

Planning is crucial and I make at least one visit to the cliff tops overlooking the stack to watch the interaction between flood and ebb tides. I look for semi-submerged skerries – small rock islands – that provide channels of lea or black water at low tides and allow safe travel in heavy seas.

You also need to prepare for the return passage, so I use weather charts from the previous week to look for any changes in sea conditions that could change the profile of the channel I used to get there.

And finally you need some rather unorthodox equipment including 600m of 6mm polypro, a lightweight dinghy and paddle, diver's booties, a 6m cordette, a pair of Speedos, heavy-duty dry bags, 20m of 12mm polyprop, an alpine hammer, a snow bar, a selection of pegs, a chest harness/inverted Gri-Gri combo and a big grin.

You're the only professional sea stack climber – why don’t more people do it?

You need a comprehensive understanding of the sea, good mountaineering and rock climbing skills and a level of self-reliance to be able to do it and I suspect the unpredictability and the nautical challenges are the main reasons why stack climbing's not done by more people. But more people should do it, because it’s incredible.

by Will Gray

This article first appeared on https://www.redbull.com. The original can be read here.