Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

Weather Wizards: High-Altitude Forecasting

This article first appeared on Explorersweb.com. The original can be read here.

High-altitude mountaineering has evolved since George Mallory gamely trudged up the Rongbuk glacier in 1924 towards his death, but despite satellite phones, bottled oxygen, plastic boots, acclimatization protocols and other lifesavers, one factor remains beyond human control: Nature itself. Weather, in particular, decides the fate of many climbs, and many climbers.

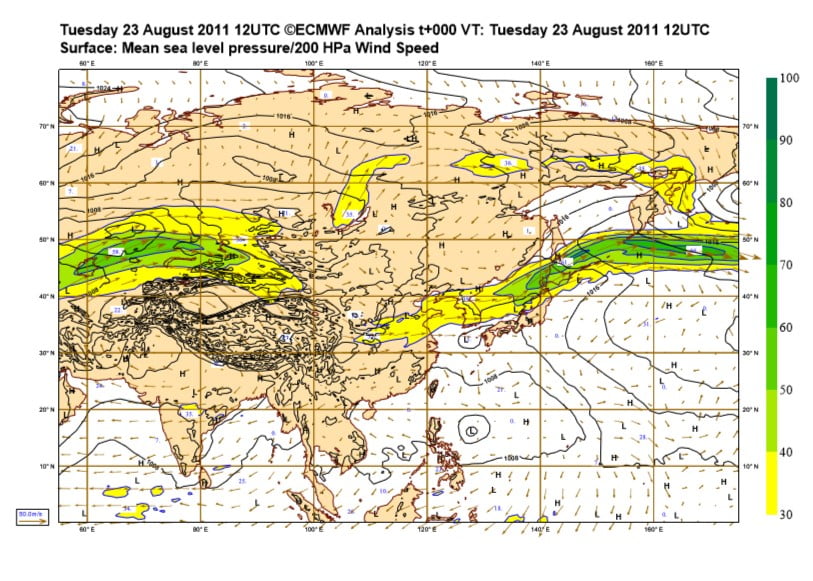

The chart shows the position of the jet stream over Himalaya when Gerlinde Kaltebrunner climbed K2. Credit: Karl Gabl

The chart shows the position of the jet stream over Himalaya when Gerlinde Kaltebrunner climbed K2. Credit: Karl Gabl

A calm and silent peak can turn into a blizzard-raging hell within minutes, and mountaineers in the Greater Ranges no longer just look up at the sky for a weather forecast before launching their summit bids.

Free apps may suffice for some adventures. (We covered services like windy.com in a recent article.) But above 8,000 meters, on the knife-edge of survival, all the world’s best climbers enlist custom meteorologists as part of their team. Let us introduce you to some of these wizards of weather.

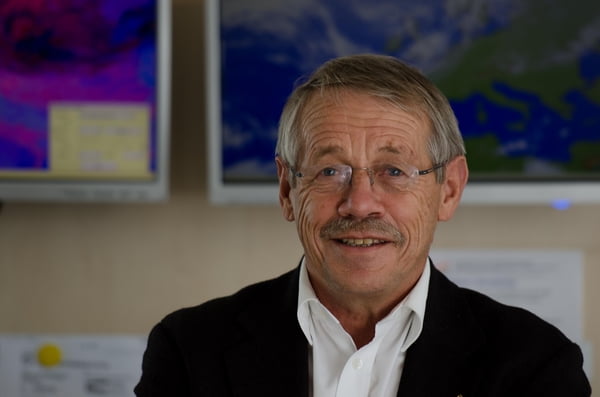

Karl Gabl (Austria)

Back in 2011, Karl Gabl of Innsbruck was already giving climbers like Denis Urubko specialized information that was key to their success and survival. “[He] guaranteed us about one-and-half days of the acceptable weather,” Denis Urubko wrote from Gasherbrum II‘s base camp that winter. “If this came from any other person than Gabl, I’d laugh. But… that was Karl, and he’s a magician.” Based on Gabl’s encouraging advice, Urubko, Simone Moro and Corey Richards hurried up the mountain without even proper acclimatization and reached the summit three days later. Moro has used Gabl as his weather guru ever since. “Karl Gabl is never wrong,” Moro claims.

Many of Europe’s climbing big guns similarly praise Karl Gabl’s role in their Himalayan successes. Although Gabl is officially retired, he continues to forecast for those he calls his “children” — mountaineers to whom he has taken a shine.

“This year I sent many forecasts, from Denali to Peru to the Himalaya, for Thomas Huber, Hansjörg Auer, David Lama, Thomas Lämmle, Andy Holzer and many others,” Gabl told ExplorersWeb.

Born in 1946, in the skiing mecca of Sankt Anton am Arlberg, Gabl began as a mountain guide, alpinist and a bold skier – his notable descents include 7,485m Mt. Noshak in Afghanistan — before earning a PhD in meteorology from Innsbruck University. He later became the head of the Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics (ZAMG). His main motive for helping climbers, however, was more personal: In 1976, his cousin died in an avalanche.

As word spread of Gabl’s meteorological clairvoyance, he became an essential member of many Himalayan expeditions. “It is not necessary to get a forecast every minute,” he explains. “Normally I am in contact with my friends – I should say my children because of my age – on the way to Base Camp only when the weather is really bad.”

He also rarely forecasts during the acclimatization phase. As they start to climb in earnest, he gives detailed updates every three to five days. Sometimes he also forecasts on summit days.

Gabl told ExplorersWeb that, like all meteorologists, he works with different models. In summer, he watches carefully when different models show different results. “Forecasts for the upcoming hours, or “nowcasting” as we meteorologists call it, make no sense in high mountains because the summit climb usually takes three days or more. Gerlinde [Kaltenbrunner]’s bid on K2 took seven days.”

It’s particularly challenging, he says, to predict heavy snowfall or thunderstorms a day in advance, as well as local effects such as drifting snow and fog.

Do not look for his fees or conditions on Gabl’s personal website or social media, because he does not work that way. “My forecasts do not cost anything,” he said. ”As a “parent”, I do not ask my children for money. For me, the best message I can get from expeditions is: “We are going home,” not “We have been on the summit.”

Vitor Baía (Portugal)

Basque climber Alex Txikon has relied on Vitor Baía‘s advice on all his latest winter expeditions. We asked Baía how meteorologists interpret models and charts, in remote places where conditions vary by the hour and sometimes from ridge to ridge.

“Summit bids on 8000’ers are best launched when low-pressure fronts are arriving or fading away,” he says. “That’s when winds tend to die down. Those situations are particularly intense in winter, and so weather windows are very short. On winter Everest, for instance, charts show about one good day in five years. In Pakistan, further north, those winter weather windows may be slightly longer, such as when Txikon launched his summit push on Nanga Parbat during an extraordinary three-day weather window.”

He adds that reliable information cannot be given far in advance, in any season. “The key to succeed on an 8000’er is to be there, armed with loads of patience, check conditions every day, gather information and be ready to jump when the window opens.”

During the summit push, wind speed is a crucial concern: over 40kph is usually too high, he says. “One wants a clear day on the summit, especially in the Karakorum, because a significant number of accidents take place during descents in foggy or whiteout conditions, when climbers can’t find their way back to lower camps.”

Thermal inversions, when clouds fill the valleys and the summits clear, are ideal days, although winds often rake the upper sections of the peak.

Born in Portugal’s Serra da Stella, Baia took up mountaineering in the 1980s, paragliding in the 1990s and meteorology right afterward. He began checking conditions to help good friend and 14×8000 summiteer Joao García. He was so successful that other climbers soon came to him for reliable, personalized forecasts during their Himalayan expeditions, including Mario Panzeri, Edurne Pasaban, Carlos Soria, Peter Hamor, Horia Colibasanu and Ivan Vallejo.

“I send simple, factual reports, usually texting the climbers’ satellite phones. Basically, I tell them if the weather is going to be good or bad, plus any problems they may find (high winds, bitter cold or too-warm temperatures). I also adapt myself to the climbing team’s criteria and experience: The notion of good weather is not the same for Alex Txikon as for a climber on his first 8000’er.”

Just before their summit bid, Baía does speak to them on the phone, in order to gather useful details of their route — length, expected hours of climbing and vertical metres to cover.

He cites the NOAA’s GFS model as his main source, but he also draws on the years of experience forecasting for others and for himself. “I am used to Himalayan weather patterns and may be aware that, for instance, winds rolling to the north in Nepal usually bring good weather,” he says. “Above everything else, I’ve learned a great deal from decades of paragliding.”

Michael Fagin (United States)

Michael Fagin from EverestWeather has been providing weather forecasts for Everest expeditions since 2003. Fagin and his associates also cover elsewhere in the Himalaya, the Karakorum and in major ranges around the world. The cost of EverestWeather’s forecasts start at $75.

His clients vary from individuals like Ed Viesturs and Jimmy Chin to large commercial teams. Sometimes, he even keeps track of snow forecasts for local schools. Fagin checks several weather models throughout the day, then sends his report to the climbing teams. While he is not against computer-generated, free online forecasts, he points out the shortcomings of those websites. For example, they usually use a single model rather than multiple programs; they don’t differ between geographically close areas that may show different weather patterns; they can’t spot phenomena such as cyclones forming in the area and they assign no probability percentage to their forecast. “These automated computer models are not looking at the big picture,” Fagin’s website explains.