Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

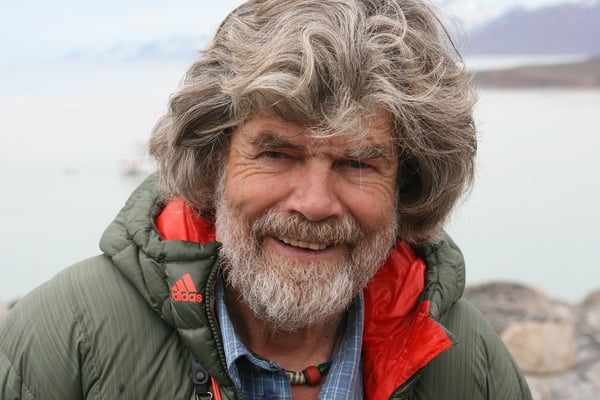

Reinhold Messner - Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Ash Routen discusses with Reinhold Messner, arguably the greatest high altitude climber of all time, success versus failure, the difference between suffering and fun, and the powerful sense of history that has underpinned his mountaineering philosophy.

As I dial the number, I draw a sharp intake of breath. I'm hoping to make sense, and I'm keen to make the best of this opportunity. I doubt it will come again. A moment later I'm chatting with Reinhold Messner - the first to climb all of the world's 14 highest peaks, and the first to stand atop Everest without Oxygen. Don't forget the crossing of Antarctica, the Gobi desert, and the walk across Tibet too. Remarkable. But that's not what he tells me "I don't think that I am a special man and I don't think I'm the most adapted person for doing high-altitude or great adventures".

Mountaineer Legend Reinhold Messner on 25 October 1993 in Nepal | usage worldwide. PHOTO: Udo Bernhart

Mountaineer Legend Reinhold Messner on 25 October 1993 in Nepal | usage worldwide. PHOTO: Udo Bernhart

I set up this call with Messner to get a sense of his philosophy on adventure and expeditions, and how he prepared for them. It's part of a longer-term project where I'm talking to people who have excelled across Polar, Ocean, Desert, and Mountain environments.

As we begin Messner chirps "I think the mental approach is more important than the physical approach, especially for these extreme adventures". So I press a little more on the topic of mental preparation before an expedition.

"All of us are identifying more and more with our challenges, so we look at the pictures, we study the history, we go into the monsoon situation, maybe there is a monsoon in the period and we are there. If I am not able, in advance, to imagine everything that can happen, where I'm going and where the difficulties are I'm not well prepared for an expedition. It's clear that, physically, you can run up mountains, like Peter Habeler and I did, we are running uphill, very steep mountains at home for training the muscles and, also, naturally, the heart and the lungs, and so on. But, the identification with what we tried to do, with what our plan was, was much more important."

Photo: Reinhold Messner Collection

Photo: Reinhold Messner Collection

Like many successful alpinists it's clear that Messner approached his climbs with an eye for detail and planning, but he seemed to allude to going much further, reaching back into the history books to find clues from the past.

"All my dreams, all the expeditions I did, all the climbs I did, and everything else, they were built on everything that happened before. Before crossing Antarctica, I studied all Shackleton's trips, but also Amundsen, Scott and so on, so I had a very strong possibility to be there before going there."

Understanding and 'living' the expeditions of the past as preparation is one thing, but I wondered how Messner managed to put his plans into action in extreme and uncontrollable environments. Many of his high altitude contemporaries died in their prime. Did he develop specific mental skills?

"I don't think that I am a special man and I don't think I'm the most adapted person for doing high-altitude or great adventures. But I was really lucky. I only understood it much later, that between my fifth and fifteenth year of life I did many middle-class, easy climbs, so an instinct came up, an instinct with nature and with wilderness. I was not the best climber, but I was very strong in feeling where I should go, where the route was, what is the weight of the wind, where are the loose rocks and where are the good rocks? All these instincts are in my being without a concrete learning. I got it also in the decades later when I did different activities, like high-altitude climbing and desert crossings."

East Rombuk Glacier, Everest north side, 1980

East Rombuk Glacier, Everest north side, 1980

© Reinhold Messner Collection

This heightened awareness, whether learned or innate, was to serve Messner well throughout his climbing career.

"I think that it was also this instinct which gave me the signs to say, "Now it's time to go back, to quit. It's too dangerous, too difficult, maybe something is not perfectly organised in our own plan or own expedition." The decision to go further or to go back came quite quickly in my expeditions, not calculating, not thinking, "This is going well, this is going wrong," so in the end, I go further, or I go back. It was instinctive."

And of course with an instinct to preserve one's safety comes the inevitable requirement to face up to aborted or failed expeditions, something which Messner seems not shy away from.

"At least in one-third of my plans I failed, I have failed many times. People always say I had so many successes, but I had a lot of failures. I failed on the North Pole when I tried to cross it, from Siberia to Canada. I failed 13 times on the 8000 metre peaks. I have failed many times. I am the mountaineer or the adventurer with the most failures in his life."

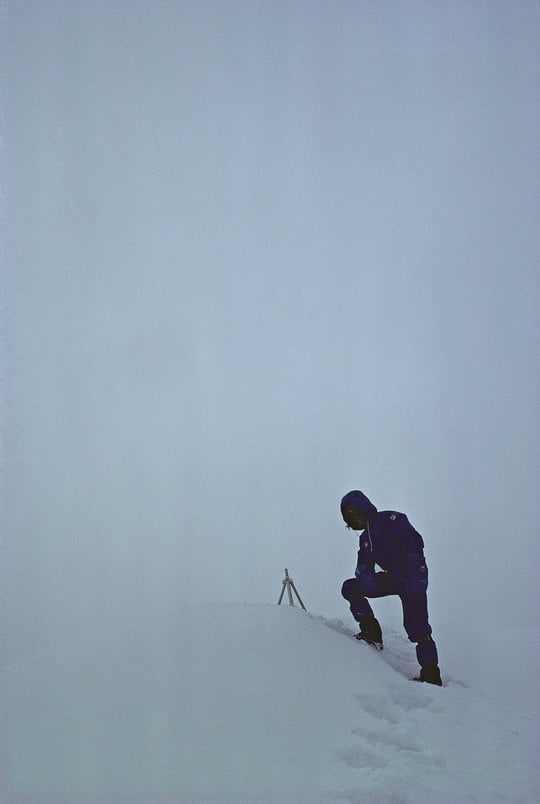

Everest summit, solo, 1980

Everest summit, solo, 1980

© Reinhold Messner Collection

Whilst failure is an inevitable and painful part of performance for any elite athlete, what of that other uncomfortable side to the games climbers play – physical suffering? Over the past twelve months I've talked to Himalayan first ascentionists, polar record breakers, ultra marathoners and desert pioneers. A common theme that always seems to crop up is suffering. For some folks it's part of the attraction to their sport, and part of an identity. For others like Messner, it seems physical suffering is an unfortunate byproduct to be endured.

"I was not driven by pains, but pains are part of the game, especially if you're going to high altitude. The lungs are hurting, the head is pained, the muscles are in pain... I am not searching for it but starting I just know it's happening. I had my experiences in the Dolomites and in the Alps, and afterwards in the Andes, and the higher I went the more I knew about the pain. It is difficult to support, but if I cannot support it I cannot do these things. So, I learnt, slowly, to cope with it and to accept it, but I did not go to high places to have these pains. I was willing to go to high places and I had to accept the fact that it's painful."

"If the young people are saying this is all fun I don't believe it. It's only a word they use because everybody uses this word today and everything has to be fun. It's not fun putting your hand in a crack and making a fist to pull you up. It's not fun in forty-below-zero, near Everest's summit without an oxygen mask and to have this cold air directly in your lungs. It's not fun having snow up to your knees, and going on your knees and elbows up a steep mountain."

Nanga Parbat solo, 1978

Nanga Parbat solo, 1978

© Reinhold Messner Collection

I began to wonder if this relationship with pain changed over time for Messner. Had his ability to suffer diminished?

"High-class mountaineering is a game of pain, and the older I got the less and less I was able to support these pains. In the young years I lost my power for rock climbing. In my young years I lost my agility for rock climbing, because I lost my toes, so I didn't especially do rock climbing and training for it. For a long time, I had the good physical ability to go far for big results, with only a little bit of food. I could withstand the cold, I could endure everything... It's not nice in Antarctica, going in a tent after a whole day of hiking and pulling a sledge, eating half-cold food, but anyway..."

"As I got older, the last thing I lost was my the ability to support pain, like in middle-old age. At 45 I was able to support more of the pain, better than at 20. But now I prefer to go to the bathroom like a man and not an animal."

If high altitude mountaineering involves physical struggle and high risk, why bother? Dare I ask the most cliché of questions – why? Thankfully I'm spared the need. Messner opens up with a riff on his philosophy for the mountains and their magnetism.

"I see, in my activity, a cultural expression or a cultural issue, and not a sporting issue. So, a history and a philosophy of Mummery, Mallory, Shipton... I speak about a few British adventurers, they give me the base to invent my challenges. I based my whole thing on what happened before, on their philosophy... My style in the mountains is following a certain tradition, and I think that tradition and mountaineering is nothing else, there are no rules, there is no right and wrong, it is only based on philosophy and history. Some of the history and some of the philosophy is what has given us the right direction for doing traditional alpinism, or traditional adventures."

"You know, the whole thing now is breaking away because 90% of the climbers go into the climbing hall and they do sport, this has nothing to do with alpinism. It's a great sport, they do competitions, it will be in the Olympics games, this climbing on the artificial holds and plastic holds."

"What is happening on Everest is pure tourism. The mountain is prepared for tourists and they pay a lot of money for using the infrastructure, made by the Sherpas, to be brought to the summit. This is also okay, tourism is okay, we alpine people live because there is a lot of tourism, and the Sherpas now, and the Sherpa families, they can make a living from this kind of tourism too."

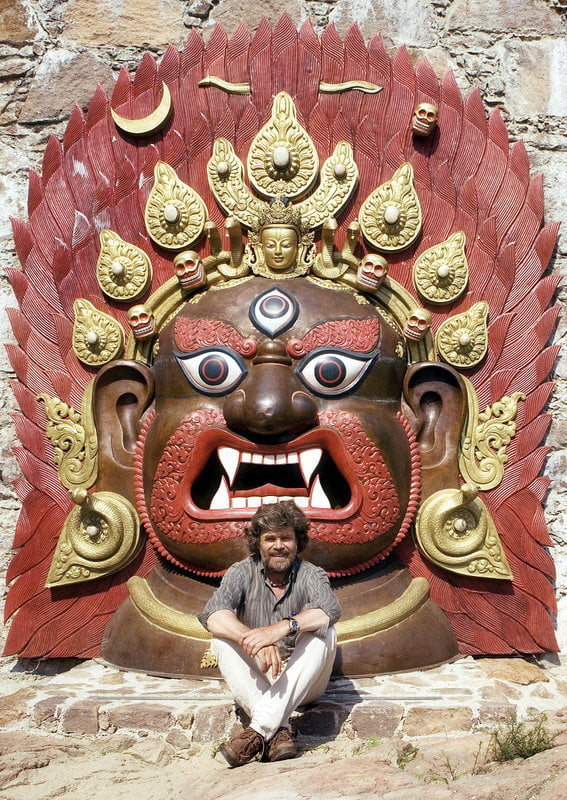

In the Firmian Messner Mountain Museum

In the Firmian Messner Mountain Museum

© Georg Tappeiner

This was not entirely unexpected, as Messner's views on the purity of 'traditional adventure' have been described in many of his works such as the 1971 Mountain Magazine manifesto on alpinism The Murder of the Impossible.

Further, his keen appreciation of mountaineering and adventure history is not surprising given that he has created and funded a series of six mountain museums across northern Italy. This appreciation is something that Messner later goes on to tell me was a driving factor for all of his expeditions.

"But, if somebody likes to do some traditional activity they are out of these pistes, which they build on the 8,000 metre peaks, Mont Blanc, on Aconcagua, and so on… If you are out of it you have to base your activities on something, maybe on feeling you are the greatest, I never had this feeling, and I built it up on the ideas that were born long before me, on the philosophy, which is a sombre philosophy, which people evolved for approaching the mountains through the 17th and during the 18th century, and so on, and afterwards the whole history. I am still enthusiastic now about the whole mountaineering and adventure history."

Now well into his Seventh decade, Messner must make do with living vicariously through adventures of the past.

"I bought a book about Frank Wild, who was the right hand of Shackleton in the dramatic endurance expedition in Antarctica. What I think about this, is that for me it's quite like going on this expedition; I sit at home but in my mental pictures I am in Antarctica, speaking with Frank Wild and knowing him. I can know him because, for me, this history, the old stories, are at least as important as doing it by myself."

From a few minutes of conversation, I had learned a great deal about Messner's preparation, mental capacity, mountain instinct, ability to suffer, and reverence for the early pioneers. But it was this latter point that he spoke about with the most passion. The narratives created by those that have gone before are what drew this man towards the extreme regions of our planet to undertake serious and exploratory adventure - something that Messner conveyed a number of times.

Leo Dickinson, the director of Everest Unmasked, a documentary about the first oxygenless ascent of Everest once quipped "Messner is the most driven human being I've ever seen on the planet". Perhaps the essence of what drove Reinhold Messner to great heights and extreme latitudes was at least in part a deep appreciation for the historical context of adventure.

"All my activities, especially things I do with new routes and new styles in the high mountains, they are based on history. So, I have in me the whole narrative and out of the narrative of what happened in the centuries before my active time came my new plans, the ambitions, and the challenges that I tried to fulfil."

Messner's detractors often accuse him of unnecessary hubris, but his is a philosophy I can identify with. To stand on the Shoulders of Giants.

This article first appeared on http://www.ukclimbing.com.The original can be read here.