Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

One Man’s Attempt to Solve a Mystery at the Top of Mount Everest

THE THIRD POLE

Mystery, Obsession, and Death on Mount Everest

By Mark Synnott

In 1924, no one had ever set foot atop Mount Everest, the highest spot on Earth. By then, America had reached the North Pole. Norway had won a bitter race to the South Pole. Everest was “the Third Pole,” and the first person who reached the top would win fame for himself and glory for his nation.

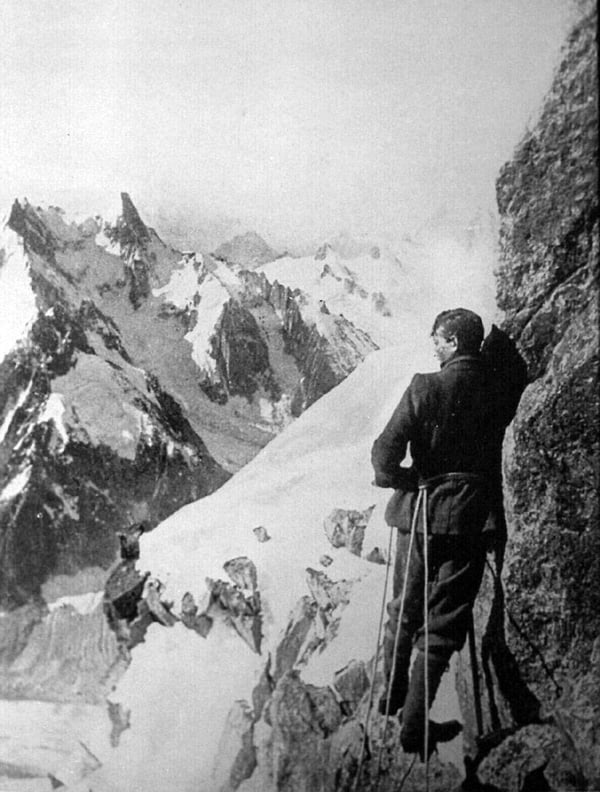

This file photo dated 1909 shows British mountain climber George Mallory, who died while scaling Mount Everest in 1924, on the Moine ridge of the Aiguille Verte mountain in France.Credit...Herald/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

This file photo dated 1909 shows British mountain climber George Mallory, who died while scaling Mount Everest in 1924, on the Moine ridge of the Aiguille Verte mountain in France.Credit...Herald/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

A century ago, expeditions to the world’s far corners carried all the excitement of a journey to the moon or Mars today. England had always prided itself on its exploring heritage, but the early 1900s were dark years for English exploration. An English team led by Robert F. Scott had reached the South Pole only to find that the Norwegians had been there already, and then Scott and all his men had died of starvation on their return trek.

The Great War brought a halt to all such wandering. England emerged from the war years stunned and reeling, with hundreds of thousands of its brightest young men maimed or killed. It was a perfect time for a hero who could rouse the nation’s spirits.

In his new book, “The Third Pole: Mystery, Obsession, and Death on Mount Everest,” the author and adventurer Mark Synnott skillfully describes early-20th-century exploration, then dives into a story about Everest that merges mystery, adventure and history into a single tragic bundle.

A mountaineer and rock climber himself, Synnott and a team set out to scale Everest in 2019 in the hope of sorting out what had happened on an ill-fated expedition up the mountain a century ago. In 1924, an English team paused just short of Everest’s summit. The climbers’ tweed jackets and leather boots would have looked to modern eyes as if they might perhaps be warm enough for an afternoon’s sledding in Central Park. Twice before English expeditions had taken on Everest, in 1921 and 1922. Twice before they had failed. Now, assaulted by a storm and battered by illness, they were near to giving up again.

The 1924 team was running out of time, as the summer monsoon season approached. George Mallory, the team’s leader and best climber, invited Sandy Irvine, the youngest of the group, to join him for one last try to reach the top. The summit lay about 1,000 vertical feet above them. The two climbers set off on the morning of June 8.

They disappeared into swirling clouds, but for a moment the clouds lifted. One team member, thousands of feet below, saw two tiny figures moving forward and “going strong.” Then the clouds descended. Neither man was ever seen alive again.

George Mallory’s body was found in 1999 but Sandy Irvine’s body was not, nor was the Kodak camera he carried, nor the film inside, which some experts believed might still be salvageable.

When many books have been written on a subject, like Everest, we turn to a new one largely in the hope that the author will make a good guide and traveling companion. Synnott measures up nicely. His rock climbing and mountaineering résumé includes dozens of international expeditions, and he wrote a book called “The Impossible Climb,” about the climbing superstar Alex Honnold.

Synnott is honest, too. “Truth be told,” he writes, “I wasn’t interested in Mount Everest at all.” Everest, in his view, was a place for novices with too much money and too little skill. Let someone else take selfies at the summit. Synnott’s wife, who also had an adventure-driven lifestyle, felt the same disdain: “Everest? Really? That seems so unoriginal and not you. Hasn’t everyone already been there and done that?”

But Synnott persuaded himself that this venture would be different. The summit wasn’t the point; the search was the point. Other expeditions had tried to find Irvine’s body, but Synnott had devised a new strategy, with the help of a friend and fellow rock climber who was also an expert drone pilot. Could a drone be modified to cope with Everest’s thin air and high winds so that it could locate Sandy Irvine’s body?

Though Synnott has no patience for what he calls “dilettante mountaineers,” high peaks are so dangerous that even experts can run into trouble, and in “The Third Pole,” Synnott recounts what happens when climbers get into trouble. He describes horror stories about frostbite and strokes (blood clots are more likely at high altitudes) and oxygen tanks that hit empty at the worst possible moment. One mountaineer in Pakistan was caught in an avalanche and “buried up to his neck in snow that had instantly set firm like fast-acting concrete.”

Reading about all of this is great fun for those of us who live in what Synnott calls “the horizontal world.” Safe at home, we settle in contentedly to hear about someone else’s calamity. (George Orwell captured a similar mood in “The Decline of the English Murder”: “Your pipe is drawing sweetly, the sofa cushions are soft underneath you, the fire is well alight, the air is warm and stagnant. In these blissful circumstances, what is it that you want to read about? Naturally, about a murder.”)

George Mallory is remembered today mainly for his statement to a New York Times reporter about why he wanted to climb Everest: “Because it’s there.” But Mallory was ambivalent about returning to Everest (on his second expedition, seven porters had been killed in an avalanche). “Because it’s there” was less a credo than a brushoff.

Mallory squeezed a lot into his short life. He fought at the Battle of the Somme, where 20,000 Allied soldiers died in a single day. He hung out on the fringes of the Bloomsbury crowd (he wrote a passable biography of James Boswell), he was a formidably skilled rock climber and he was so handsome that strangers did double takes. (The writer Lytton Strachey had a powerful crush on Mallory: “Mon Dieu — George Mallory — When that’s been written, what more need be said?”)

Sandy Irvine remains a more shadowy figure. Only 21 years old at his death, he was a gifted engineer who could improve anything (including the newfangled oxygen tanks that mountaineers were just learning to use). Before Everest he had never been more than 5,500 feet above sea level, but perhaps he was eager for a change of scene — Irvine had been carrying on an affair with his best friend’s stepmother, and Mallory’s invitation to climb the mountain arrived just as the scandal was breaking.

Synnott knows how to keep readers turning the pages, and they will speed their way to his mystery’s resolution. But any Everest story today has an unavoidable dark side. Mallory’s team had a towering mountain and a vast landscape nearly to themselves. Synnott’s team encountered crowds and one site that “looked more like a third world landfill than the staging point below the most glorious summit in the world.” Worse yet, climbers on Everest today know they will encounter dead or dying adventurers along their way. Kitty Genovese scenes play out on the world’s rooftop.

How many climbers will forfeit a chance at the summit to try to save a dying stranger’s life? Not many, it turns out.

Synnott faced no such dilemmas with struggling climbers, but he passed half a dozen frozen corpses on his climb. At one point he sank to the ground, exhausted, alongside a dead body. At first he maintained a respectful distance. Then he gave in and leaned against the dead man, the living man resting his weight against the icy corpse.

Everest will always be the top of the world, but it has become a difficult place to savor.