Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

Why the Mountaineering World Can’t Stop Talking About Denis Urubko

Denis Urubko brought the Karakoram climbing season to an emphatic crescendo when he blazed a new Alpine-style route on Gasherbrum II (8,034 meters), solo and without oxygen.

Urubko, left, with Elisabeth Revol and Adam Bielecki after a successful rescue on Nanga Parbat in January 2018.

Urubko, left, with Elisabeth Revol and Adam Bielecki after a successful rescue on Nanga Parbat in January 2018.

The route is historic by itself, but it’s the manner in which Urubko completed it that has set the mountaineering world abuzz. He left his radio and satellite phone in base camp and brought no sleeping bag, water or stove. With only a handful of energy gel packets for sustenance, he climbed 24 hours to the summit and downclimbed 18 more to return via the normal route. His girlfriend, the alpinist María “Pipi” Cardell, told the Spanish-language climbing site Desnivel that Urubko “climbed the summit pyramid in a straight line, as he planned not to coincide with any of the existing routes or variants.”

All this after first tagging the summit via the normal route for “a nice acclimatization,” and then participating in three successful rescues while he waited for conditions to improve. He’d planned to open the new route with Cardell at a more measured pace, but she suffered a debilitating back injury on the weeklong trek to base camp. When it became clear in mid-July that she was not fit to climb, Urubko decided on his solo lightning strike.

“Originally, María and I planned three to five days. But going solo has certain advantages. I could go non-stop, full blast,” Urubko said in a brief interview with the Russian-language site, Mountain. “Despite the problems, I managed to keep the fire alive. I won’t back down when it is possible to realize a dream,” he said.

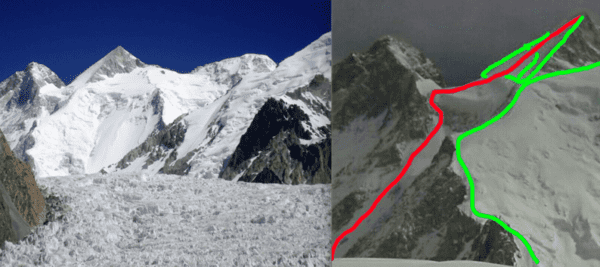

Urubko’s view of Gasherbrum II’s near-perfect summit pyramid (left). The new route he named “Honey Moon” is marked in red in the image at right. The more common lines are marked in green, including the normal route along the southwest ridge. Courtesy Denis Urubko and Mountains.RU

Urubko’s view of Gasherbrum II’s near-perfect summit pyramid (left). The new route he named “Honey Moon” is marked in red in the image at right. The more common lines are marked in green, including the normal route along the southwest ridge. Courtesy Denis Urubko and Mountains.RU

Urubko’s line brought him straight up the middle of the western face of GII’s distinctive summit pyramid. “I crossed the first small bergschrund (6,050 m) at the foot of the wall, then moved up ice and firn, past seracs and avalanche-prone slopes,” he said. “A kilometer drop lay beneath my feet. I reached the top at 8:40 p.m. The effort exhausted me.”

Urubko has now climbed GII four times, including a 2001 speed climb in which he set the record for the fastest ascent—seven hours and thirty minutes up and four hours down—and more significantly, the first winter ascent in 2011, with Italian Simone Moro and American Cory Richards. Theirs was the first winter summit of an 8,000-meter peak in the Karakoram Range, which lies some 500 miles north of the other high Himalayan peaks in Nepal and Tibet.

His third summit came on July 18 as part of his acclimatization regime and to scout his planned descent via the normal route. Still, after reaching the summit via his new route shortly before 9 p.m. on Aug 1., he nearly lost his way back down.

The wind was ferocious, limiting visibility. Even though he’d climbed the normal route just days before, he was disoriented enough that he had to stop and rest for hours before he could ascertain the route.

He waited until first light, then continued down to meet Canadian Don Bowie, American Matthew James and Lotta Hintsa of Finland in Camp 1. The trio had planned to meet Urubko on the summit but aborted their attempt due to dangerous conditions. Days of unusually warm weather had turned the Gasherbrum glacier to slush and opened dozens of new crevasses. Bowie and the others assessed the avalanche risk as extremely high. After careful study, Urubko judged the conditions on his new direttissima acceptible, though by no means ideal.

“Every project has its surprises and troubles,” he said, referring to Cardell’s injury, the unstable conditions and the accumulated fatigue of three difficult rescues in a period of five days, the first an all-night affair that Rock and Ice called a “miracle rescue.”

Fresh off his acclimatization summit, Urubko raced with Bowie and two others to reach Italian ski mountaineer Francesco Cassardo, who had tumbled 500 meters down the face of nearby Gasherbrum VII. The rescuers worked through the night to bring Cassardo down the glacier on a makeshift litter, where he was evacuated by helicopter.

Next up was Lithuanian Saulius Damulevicius, who was suffering from high altitude pulmonary edema. Urubko and Catalan ace Sergi Mingote climbed to his aid. The next day, they assisted a Pakistani climber who had run into trouble in an icefall. These efforts no doubt drew heavily on Urubko’s reserves, but there was never any question whether he would answer the call. “He has been raised and trained in the old Soviet school of mountaineering—he helps because this is what you have to do,” the Twitter channel RussianClimb explained.

Urubko is Russian by birth, but after the dissolution of the Soviet Union he climbed under the flag of Kazakhstan, a former Soviet Republic with a subsidized army climbing team and some of the biggest mountains in Central Asia. He’s now a dual national of Russia and Poland, which gave him a passport on the strength of his winter climbing exploits. He was a key member of the 2018 Polish Winter K2 expedition, which was the setting for two of the most dramatic incidents in Urubko’s extraordinary climbing career.

The first was the rescue of French climber Elisabeth Revol, in which Urubko and his K2 teammate Adam Bielecki flew by helicopter to neighboring Nanga Parbat and climbed through the night to help Revol, who was incapacitated above 6,000 meters. They were unable to reach her partner Tomasz Mackiewicz, who was lost above 7,200 meters.

The next took place a month later when Urubko, chafing at the slow pace of the Polish team and driven by his particular definition of winter—he holds the season ends at the end of February, while the Poles’ more generous definition extends another three week to the vernal equinox—abruptly decided to launch his own summit bid, solo and against the orders of his team leader.

Urubko charged up the mountain without radio, satellite phone or tracker. When he returned to camp two days later, having turned around well short of the summit, he said he’d gone incommunicado because if anything went wrong he didn’t want his teammates to risk their own lives to come to assist him. It was a strange assertion coming from a man whose reputation rests in large part on his high-altitude rescues. Urubko has pioneered five new lines on 8,000-meter peaks and climbed all of the world’s 14 highest peaks without oxygen, but many of his most memorable exploits are the rescues he performed between those summits. Hence Rock and Ice’s description of Urubko as “one of the strongest Himalayan climbers of all time and perhaps the most experienced high-altitude rescuer ever.”

Last week on Gasherbrum II, Urubko again left the communications gear in camp. This was in part to save weight—he didn’t even take water for God’s sake—but it was also an aesthetic choice. Knowing that he was completely on his own was an essential piece of Urubko’s vision for this climb.

Still, for Cardell and the trio of climbers in Camp 1, it made for a nerve-wracking silence. As Angela Benavides wrote on Explorersweb, his route was largely out of sight from Camp 1, and the climbers there caught only a glimpse of him around noon on August 1, somewhere above 7,000 meters. “Concern grew among the climbing community, although not a single voice expressed it aloud,” Benavides wrote. “Urubko is not any other climber, they said. He’s Denis—the one who rescues others, never the one in need.”

The hours ticked by until finally, on the afternoon of Aug. 2, Urubko reached his companions in Camp 1. He’d been climbing for 42 straight hours.

A week after the ascent, Urubko’s new route on GII is already the stuff of legend. Many more details are still to come, but for now, Urubko is content to savor the moment. “I really just wanted to realize my idea of freedom,” he told Mountain. “It’s like an artist drawing a single beautiful stroke about which he’s dreamed for years. Yes, it would push me to the limits of my strength, but that’s what makes mountaineering worthwhile.”

by JEFF MOAG

This article first appeared on http://www.adventure-journal.com. The original can be read here.