Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

Crossing Antarctica: How the Confusion Began and Where Do We Go From Here

This article first appeared on Explorersweb.com. The original can be read here.

On December 27, Colin O’Brady wrote triumphantly on Instagram:

“The wooden post in the background of this picture marks the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf, where Antarctica’s land mass ends and the sea ice begins. As I pulled my sled over this invisible line, I accomplished my goal: to become the first person in history to traverse the continent of Antarctica coast to coast solo, unsupported and unaided.”

In fact, the American was hundreds of kilometres from sea ice. He was still on land ice, and ever since leaving the South Pole, he had followed a graded and marked road built by the U.S. government in 2005 — something he never mentioned to the media or to his online followers. He had neither crossed the continent nor been unsupported.

O’Brady on the SPoT road

O’Brady on the SPoT road

Two days later, the Briton Lou Rudd finished the same route, in what the media had predictably deemed a race. Rare these days, the two polar expeditions had drawn the attention of mainstream news organizations, especially The New York Times. The NYT seemingly became interested in Antarctic crossings after Henry Worsley died from peritonitis in January 2016, after one such attempted crossing. A 20,000-word story in The New Yorker gave Worsley’s quest further legitimacy. This season, the NYT gave the two rivals major coverage but — except for an opinion piece by noted writer David Roberts after they finished — added little context and never mentioned anything about O’Brady and Rudd using a graded road. Other news sources, from CNN to NPR to The Guardian and The Telegraph, simply bought into the expeditions’ pr claims and touted them as first true solo crossings of Antarctica.

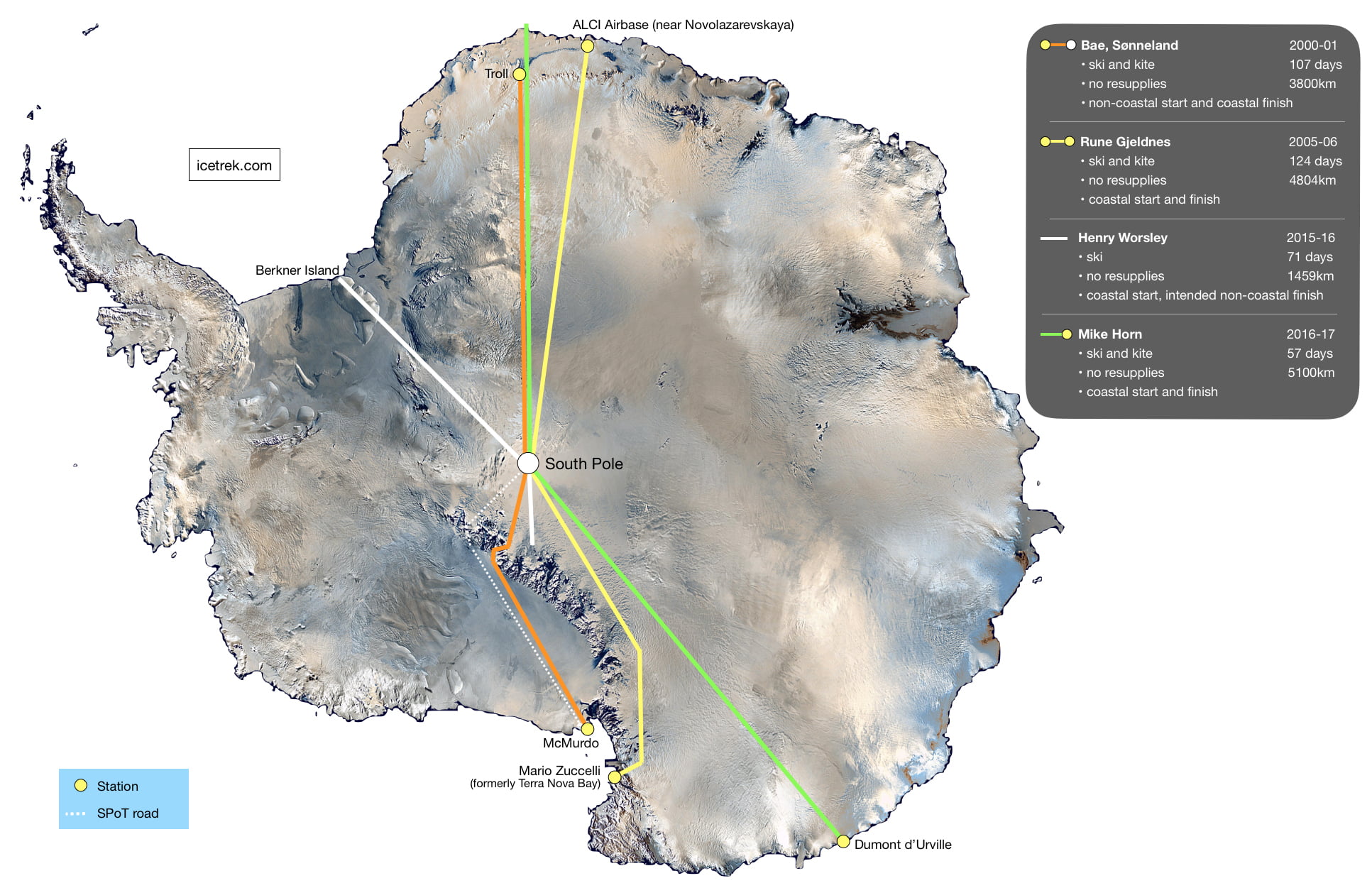

Some full and partial crossings of Antarctica: Bae & Sonneland, Gjeldnes, Horn and Worsley. Map: Eric Philips/Icetrek

Some full and partial crossings of Antarctica: Bae & Sonneland, Gjeldnes, Horn and Worsley. Map: Eric Philips/Icetrek

For decades, adventurers have manipulated language and withheld information in order to present their journeys in the most flattering light. Using subtle qualifiers that mean something to them and their competitors and not much to anyone else, they sought to gain sponsorship and enhance reputation. We have already seen this in increasingly conditional ascents of Mount Everest, but polar skiing is even more alien and esoteric, a niche culture of arcane do’s and don’ts whose roots stretch back into the last century.

The only serious attempt to formalize these practices was the Rules of Adventure, [Editor’s note: Part of ExplorersWeb’s legacy that we are in the process of reassessing] but some of these rules contained questionable assumptions and biases, were not widely accepted in the community and have been largely overtaken by developments in the last decade.

Normally, in any field, if someone wants to claim a first, they do so on a track of similar length, and in the same style as their predecessors. You do not contrive a route that is both geographically shorter and artificially easier, thereby choosing just the rules that suit you.

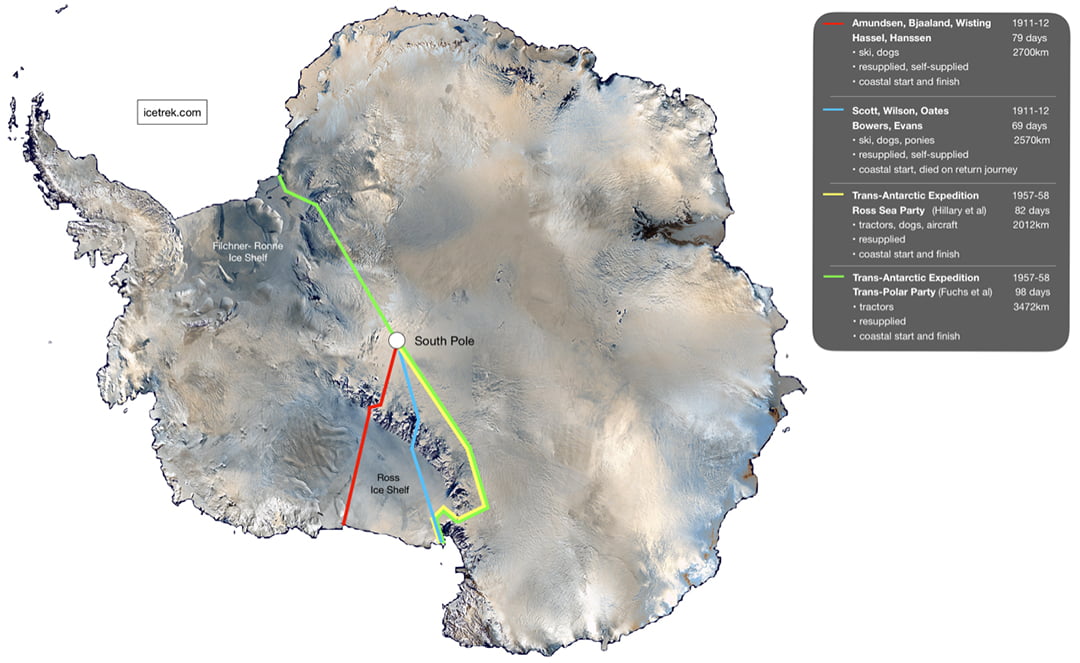

Classic routes: Scott, Amundsen and the first mechanized crossing of Antarctica. Map: Eric Philips/Icetrek

Classic routes: Scott, Amundsen and the first mechanized crossing of Antarctica. Map: Eric Philips/Icetrek

Crossing Antarctica – History & Geography

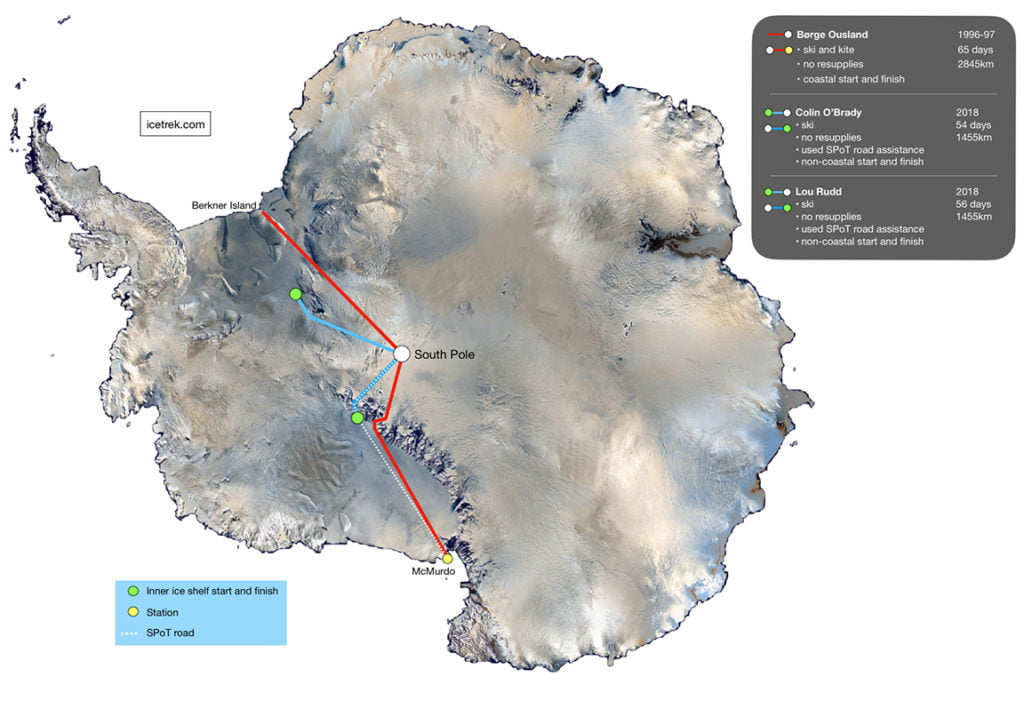

The first two mechanized crossings of the continent traversed the entire Ross Ice Shelf: Vivian Fuchs in 1955-58 and the Transglobe expedition in 1980-81. The first successful crossing of Antarctica by dogsled and ski — the Mørdre brothers in 1989-90 — included both the Filchner and Ross Ice Shelves. The first successful solo ski crossing, by Børge Ousland in 1996-97, likewise included both the Filchner and Ross Ice Shelves.

First mechanized expedition, 1955-58: crevasses aplenty

First mechanized expedition, 1955-58: crevasses aplenty

The Antarctic ice shelves are land ice — sheets of glacier ice that have slid down from the higher reaches and now jut out over the sea. They have been attached to the continent for 100,000 years and are part of it. They are certainly not “sea ice”, which is the seasonal material that freezes from salt water every winter and mostly melts every summer.

Ice shelves, meanwhile, are no more impermanent than the few metres of ice atop Mount Vinson. O’Brady climbed Vinson in January, 2016: Did he stop at the last rock? Or did he go right to the highest point of ice on the summit, like everyone else does? Yes, photos show he continued up past the rocks and stood on the ice, because that ice is part of the mountain.

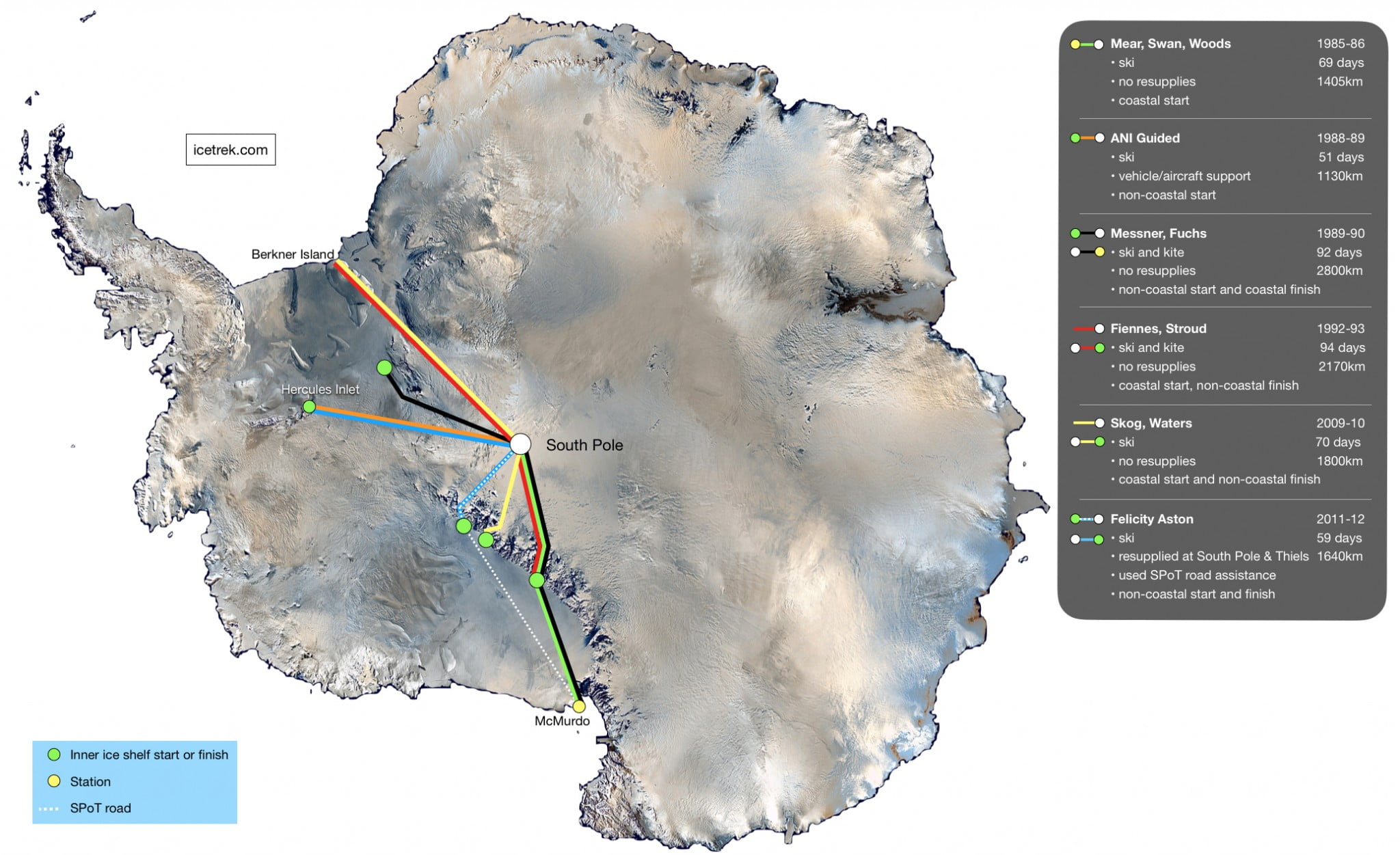

That the ice shelves were part of the Antarctic continent was accepted both by explorers like Shackleton and by the first late-twentieth century adventurers who attempted continental crossings: Messner and Fuchs in 1989-90, Ranulph Fiennes in 1992-93 as well as Børge Ousland and the Mørdre brothers, all of whom were building on the 1985-86 Footsteps of Scott expedition, where Roger Mear, Robert Swan and Gareth Wood skied across the Ross Ice Shelf to the South Pole, in a time before even the GPS.

Hercules Inlet – Money Talks

In 1988, the fledgling logistics operator Adventure Network International (ANI, later to become today’s ALE — Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions) ran the first commercially guided ski expedition to the South Pole. Four guides led seven clients, using both snowmobiles and multiple air drops to greatly reduce the loads. In terms of support, this expedition was an unrepeated one-off, in comparison to later guided trips that have just one or two air resupplies but no snow machines.

As a commercial venture, the economics of that first guided trek was important for Martyn Williams, the organizer and one of the owners of ANI. He came up with the idea of starting at Hercules Inlet, mainly because it was a cheaper and easier “edge” to reach than Berkner Island, whose northern terminus fronted the open sea — a true coast. Williams and ANI gave no great thought to the geographical significance of the starting point and were generally making up these things as they went along, having fun opening up Antarctica to the world.

In the years immediately following, however, teams serious about making some major claim about their trip – first across on skis, first solo, first unsupported crossing, etc. — ignored Hercules Inlet and used Berkner Island, with only a few expeditions choosing a Hercules start. Then, in 1999-00 and 2000-01, a rush of skiers opted for Hercules Inlet, including the second and third commercially-guided expeditions run by ANI. Hercules became more popular after that.

The Messner start. Reinhold Messner, left, and Arved Fuchs

The Messner start. Reinhold Messner, left, and Arved Fuchs

The Messner Start

The so-called Messner Start that O’Brady and Rudd used is also a recent commercial contrivance. In November 1989, Arved Fuchs and Reinhold Messner arrived in Antarctica to do a continental crossing from Berkner Island to Ross Island. They planned to resupply at the Pole and use kites for the outward leg. But the DC-6 chartered by ANI was delayed fighting forest fires in California, and they had additional problems getting the plane and fuel into position for Messner and Fuchs to start at Berkner.

With time running out, they eventually dropped Fuchs and Messner at a relatively random point inland, not on any coast. Messner, the legendary alpine purist, was furious and threatened to sue, but ANI refunded him “a whack o’ money”, as Pat Morrow puts it, and all was well.

In recent times, some groups began near this random point, now called the Messner Start. Later, ALE moved the Messner Start to the inside edge of the Ronne Ice Shelf, creating an even shorter journey to the Pole than from Hercules Inlet — and still very much not what its namesake intended. About his inland start, a disappointed Messner wrote in Antarctica: Both Heaven and Hell: “If we were to reach the other side after marching 100 days, it would be no longer a complete traverse of the Antarctic.”

Fiennes & Stroud – The Goal Posts Shift

When Britain’s Ranulph Fiennes and Mike Stroud failed to make it over the entire Ross Ice Shelf in their attempted 1992-93 continental crossing, after plodding 94 days from Berkner Island, they at first admitted that their expedition had failed, 600km short of their declared endpoint of Ross Island. Both recognized that the outer edges of the ice shelves were “traditionally…considered as an integral part of any southern journey.” Only later did they spuriously introduce the idea that crossing just the land was enough. Suddenly, retroactively, the ice shelf didn’t count.

After their long and extremely arduous walk, with only minimal assistance from primitive sails, they called for a pick-up on the Ross Ice Shelf. Fiennes was already crafting the message for his public, but Stroud was more honest: “We knew in our hearts, or at least I did in mine, that we had not completed what we set out to do,” he stated. “I cannot escape the conclusion that we copped out.”

And So A Precedent Is Set, A Bad One

In 2000-01, the accomplished team of Anne Bancroft and Liv Arnesen also stopped short and made a similar claim for a crossing, though they had done a slightly different trip, kiting from Queen Maud Land. In the same season, however, Norwegians Rolf Bae and Eric Sønneland did manage to avoid shifting the goalposts: They kited the whole distance to their ship extraction point at Ross Island.

In 2009-10, Ryan Waters and Cecilie Skog went to the trouble of starting at Berkner but stopped at the bottom of the Axel Heiberg Glacier and claimed an unsupported and unassisted crossing, as they had no kites or resupplies. But as Børge Ousland remarked to me recently about both the Fiennes-Stroud and Skog-Waters trips: “I think that if these two teams thought that a full crossing would be just from mountain edge to mountain edge, they would never have started from the northern shores of Berkner Island, adding several hundred kilometers to their journey.” The inconsistency of starting at one outer edge but stopping at a convenient inside edge and calling it good is not appropriate for a major claim reliant on geography.

Recent full and partial Antarctic traverses, plus the Mear-Swan-Woods route from the Ross Ice Shelf to the South Pole. Map: Eric Philips/Icetrek

Recent full and partial Antarctic traverses, plus the Mear-Swan-Woods route from the Ross Ice Shelf to the South Pole. Map: Eric Philips/Icetrek

What is “Across Antarctica” Anyway?

Start and finish points are not the only issues with some supposed continental crossings. In mountaineering terms, doing a traverse usually means that you go across the thing, up one side and down the other: maybe up the north and down the south, or east to west. You wouldn’t normally go up, say, the north ridge, come down the northeast ridge right next to it, and call it a traverse. Likewise for Antarctica, if one imposes an imaginary compass over the continent, centred on the South Pole, with four quadrants of 90° each, you would expect a traverse of the continent to cross from one quadrant into another. But a route from, say, Hercules Inlet to the base of the Leverett Glacier, or up the Axel Heiberg Glacier from its base and back to Hercules Inlet, may technically bridge quadrants, but they take place wholly within a 90° arc, meaning that they actually cross very little of Antarctica.

Impossible? Not Quite…

I wondered if O’Brady and Rudd didn’t stop to consider there was a reason that their 1,455km “crossing” had not already been done, despite previous skiers achieving greater distances without kites on other trips. Alexander Gamme, for example, went more than 2,200km, unassisted and unsupported, from Hercules to the Pole and back in 2011-12. Why didn’t Gamme instead follow the ice road and claim this grandest of prizes? Martyn Williams himself, the man responsible for the problematic Hercules Inlet route, said recently, “If the rules had been established as Hercules to Leverett, then Messner or Børge and others would have attempted it or done it years before.” Because O’Brady’s previous Antarctic experience, limited to the Seven Summits and Last Degree trips, were as a guided client, one might possibly excuse such ignorance of Antarctic history, but what was Rudd’s excuse? Their traverse hadn’t been done before because those in the game knew that it wasn’t a true crossing, so they chose not to do it.

Attempted crossings, with no kites or resupplies, that have tried to go from the outer continental edges have failed due to the mammoth distance. This distance, and limited time, is what undid Fiennes and Stroud, Ben Saunders and others. This is why such a crossing has been deemed “impossible”, a reputation on which O’Brady based his marketing (“Impossible First”). By doing so, he automatically placed himself and his objective in the context of those before him, in a community of shared standards and experiences. The value of his claim relies on their failures. But by just going from inner coast to inner coast, locations that previous aspirants deliberately avoided – and along the graded SPoT road – he has shown he is only too willing to reject the true challenge of the famous goal and disrespect all those whose failed efforts built the challenge up to what it has become. It’s claiming the big trophy without winning the big race.

Ousland (red route) vs. O’Brady and Rudd. Map: Eric Philips/Icetrek

Ousland (red route) vs. O’Brady and Rudd. Map: Eric Philips/Icetrek

When Ousland’s 1996-97 crossing is drawn on a map next to O’Brady and Rudd’s, it is clear to the onlooker that one expedition truly crossed Antarctica and the others did not. Ousland’s route is the shortest and most practical way to truly cross the whole continent. A crossing of Antarctica is a geographical challenge, with obvious natural boundaries. Those boundaries, which influence the sporting parameters of our game, are not set by money, cost or convenience. As in climbing, it is a natural line that attracts the challenger, not a contrived route done for relative ease or faster fame.

To some extent, O’Brady and Rudd have drifted off course on a current generated by others who have claimed these short and contrived crossings. One such predecessor is the Briton, Felicity Aston, who in 2012 claimed a traverse of Antarctica, with resupplies, using the Leverett-Hercules combo.

Børge Ousland on the first solo, unsupported crossing of Antarctica

Børge Ousland on the first solo, unsupported crossing of Antarctica

Unassisted/Unsupported

Historical context is important when making claims to be first, particularly when the claim relates to the feats of others. When Ousland crossed Antarctica alone in 1996-97, he achieved one of the great adventures of all time, a supreme example of humanity engaging with harshest nature in a minimalist way. The use of a sail — a Beringer sail, different and less efficient than modern kites — was considered an elegant advance in polar travel that was clearly more efficient than constant manhauling. Says Ousland now: “It did not even cross my mind that using the natural force of the wind would later be controversial.”

But in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the idea arose that sails were an artificial aid that cancelled what was then just termed an “unsupported” status. In these Rules of Adventure, the category was split into Unassisted and Unsupported, with sails, then kites, relegated to the latter, as they provided a material addition to basic legs and lungs. The term Unassisted remained to denote no air resupply, food drops, caches, vehicle following, etc.

In the polar community, the jury is still out on whether kiting qualifies as support. It’s certainly not some easy fix around the hard slog of manhauling. Most kiters will tell you that it requires training, skill, judgment and involves clear risk. At least one Antarctic kiter has been thrown, injured and dragged by his kite, and was lucky to survive. But kites also unarguably aid human propulsion and therefore are technically support.

However, this relies on a strict minimalist view of an ideal, with the body as the sole perfect state. Manhauling is so slow, and kiting is so obviously sensible in windy Antarctica, that one should probably question what is truly the perfect minimum. If pursued ad absurdum, minimalism dictates that we walk naked out our front door, swim to Antarctica, trudge barefoot across the ice, then swim home. Instead, we agree that it’s okay to carry all sorts of hi-tech gear, clothing, tents and comms, not to mention skis, to make the whole thing easier and safer.

While manhauling and not using kites has a minimalist appeal — more physiology than technology — if you use a million-dollar airplane burning thousands of dollars in fuel to fly to a contrived starting point, then blog your progress every evening with the latest comms and get picked up literally in the middle of nowhere at your nominated end, then maybe you are just confining your minimalist doctrine to a convenient and flattering industry bubble, and the whole thing loses some of its virtue. When one looks at landmark ski expeditions in recent years, the greatest ones have been the kiting trips of Rune Gjeldnes and Mike Horn, skimming across the great expanse of Queen Maud Land, tagging the Pole, needing no resupplies and venturing past even Ross Island to further coastal points, where they step aboard ships and sail home. Is manhauling really better than that?

Manhauling relies on concepts like the nobility of suffering, but paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to force ourselves to demonstrate how tough we are can seem like some game for the bored and affluent. One can only make such choices from a position of luck and privilege, and such resources might be put to better use than dragging your snacks across the snow for a couple of months while quoting Shackleton on Instagram.

The SPoT Road – It’s Support

In 2005-06, the United States Antarctic Program finally finished its South Pole Traverse road, a graded track from McMurdo station across the Ross Ice Shelf, up the Leverett Glacier and all the way to the South Pole. This was made to facilitate tractor resupply of the Pole and reduce flights. Crevasses were filled in and flagged marker posts erected every 400m in order to aid route-finding in a whiteout. It was never envisioned that adventurers would use this manufactured trail. O’Brady makes no mention of following a road in his dispatches, even though he describes the terrain and descent. But he did follow it, and in at least one photo the smooth, tracked surface is clearly visible.

The road is not just a physical aid to hauling, but helps with navigation and relieves the weight of isolation that vast Antarctica imposes on us. While some technological factors — GPS, satellite phones — can no longer be removed for safety reasons, and are stipulated as mandatory by logistics operators, a graded road with markers every 400m surely cancels any unsupported status, which is presumably why both O’Brady and Rudd failed to mention it.

A less obvious issue is the use of vehicle tracks elsewhere in Antarctica. For the last decade or so, vehicles have plied paths around Hercules Inlet, on the way to the Thiel Mountains and beyond to the Pole, as well as in parts of Queen Maud Land. Sometimes, the tracks are too rough to ski over, so are best avoided. Other times, they give a better skiing surface than the snow or sastrugi beside them. Teams using these tracks in recent years rarely say so publicly. Other expeditions have deliberately avoided them for a more honest and authentic experience. Some have done both.

The SPoT road. Photo: Eric Philips

The SPoT road. Photo: Eric Philips

Cost

The great financial cost has been part of Antarctic expeditions since day one. Money is the reason that whalers and sealers were the first to visit Antarctic environs, money is the reason that only governments could explore, map and occupy Antarctica for decades, and money is the reason for the Hercules and Messner Starts. Without lots of money, we can’t get on the plane to Antarctica in the first place. Modern expeditions leaving Punta Arenas often have a traditional drink in the Shackleton Bar beneath the Hotel José Nogueira, where Shackleton gave talks to gain more funding from potential sponsors, right up until the minute he sailed south from the docks across the road.

When Ousland set out to do it right in 1996, he too needed to raise money, because the flight from Patriot Hills to Berkner Island cost $175,000, beyond the cost of getting to Antarctica in the first place. Luckily for him, he was able to split some of the charter with the Polish adventurer Marek Kaminski, who also chose Berkner to start. So there’s no getting around the issue of money in all this and how it influences where expeditions might go, start and finish.

But the geography of Antarctica is not determined by your bank balance, your marketing team or the state of sponsorship opportunities in your home country. If you make a claim that relies on geography, then geography gets priority over cost. No one claims to be the first to do The Longest Journey I Could Afford Right Now.

Rune Gjeldnes amid crevasses

Rune Gjeldnes amid crevasses

Some Leeway – Because What Is This Really For?

Starting points have always been granted reasonable leeway. Weather or surface conditions may prevent planes from landing in a particular spot. There are slight variations on the Berkner and Novo starts, for example, but the distance is not considered meaningful, considering that any traverse from there is thousands of kilometres more. You don’t actually have to start from Ross Island with wet boots.

Agreeing on some flexibility not only allows for the reality of humans dealing with Antarctic conditions, but it indicates that these rules we seek to impose are not like cudgels with which to beat each other over the head. They are more like guides to quality, benchmarks by which we mark and make progress toward something we all recognize as better than what went before. O’Brady and Rudd’s trips are not progression, they are regression, because they avoided the very challenges inherent to the feat they claim to have achieved.

Leeway does not really extend to some of the blatantly inconsistent attempts over the years — Fiennes and Stroud, for example, and even Worsley himself who, claiming to be doing what Shackleton could not, started at Berkner Island but never intended to fully cross to Ross Island. They were simply trying to bend the rules, hoping that journalists wouldn’t notice and that their social media supporters wouldn’t care. It’s not the end of the world, after all, as polar ski adventures are not really life or death any more. They are a game for those who can afford to play them. Sporting contests have rules, if they are to mean anything, and what those rules are and how we enforce them says a lot about us.

One day, someone will walk from Berkner Island to Ross Island via the South Pole, purely on skis, without kites, roads or resupplies. That will be a significant achievement in the annals of polar adventuring. Whoever they are, they deserve a clear run at the goal, free of murky claims based on lesser feats. None of us has the right to steal that future opportunity from someone better than us.