Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

Lifelong secret of Everest pioneer: I discovered Mallory's body in 1936

Son of mountaineer Frank Smythe tells how his father spotted the remains – but decided he had to keep quiet.

Tony Smythe knew he might find secrets when he came to write a book about his father, the 1930s Everest pioneer Frank Smythe. But he hadn't anticipated they might include Frank's discovery of George Mallory's body in 1936. "I found it in the back of a diary," Smythe says. "He'd written out a sequence of letters he'd sent, so he would have a copy."

What happened to Mallory and his climbing partner Andrew "Sandy" Irvine, and whether they got to the summit almost 30 years before Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary, is the most enduring mystery in the history of exploration, and Mallory one of its most romantic figures: the Galahad of Everest. His weather-bleached remains were discovered by the American mountaineer Conrad Anker in 1999.

The crucial letter was addressed to Edward Norton, leader of the 1924 expedition when Mallory and Irvine disappeared, apparently going for the summit. An ice axe, assumed to belong to Irvine, had been discovered in 1933 by the fourth British expedition to the mountain. It was lying on rock, as though placed there, at 27,760ft, the only trace of either man above their last camp. Smythe – often described as the Chris Bonington of his day – felt sure it marked the scene of an accident and told Norton why. "I was scanning the face from base camp through a high-powered telescope last year," his letter read, "when I saw something queer in a gully below the scree shelf. Of course it was a long way away and very small, but I've a six/six eyesight and do not believe it was a rock. This object was at precisely the point where Mallory and Irvine would have fallen had they rolled on over the scree slopes."

Smythe had first-hand experience of mountaineering accidents – and what a long fall can do to the human body. In 1934 he searched for and found the remains of two Oxford undergraduates, Paul Wand and John Hoyland, who had disappeared in the Alps that summer. Hoyland was the nephew of Everest veteran and missionary doctor Howard Somervelland among the brightest climbing talents of his generation.

That episode featured in one of Smythe's books about the mountains, but his discovery of a body on Everest remained hidden. "It's not to be written about," Smythe told Norton, "as the press would make an unpleasant sensation." Smythe was right to be concerned. When American climber Conrad Anker rediscovered Mallory in 1999, photographs of his remains appeared on newspaper front pages around the world.

Smythe himself, climbing alone after his partner Eric Shipton turned back, reached around 28,200ft in 1933, sharing the prewar altitude record. On the descent he began hallucinating and was on the verge of total exhaustion when he reached safety. "Everest," he wrote in his diary, "is becoming a life's task."

Tony Smythe knew his father was obsessed with Everest, but another secret he uncovered reveals just how far he was prepared to go for another chance at the summit. After the 1933 attempt, the Mount Everest committee doubted whether the Dalai Lama would allow another expedition for many years. So Frank devised an elaborate plan to make an illegal attempt on his own in 1935 with support from handpicked Sherpas. "It was an alarming indication of Frank's desire to climb the mountain at almost any cost," his son says.

Such an attempt would, according to Tony Smythe, have ruined his father. Although a member of the Alpine Club, Frank was viewed with suspicion by the mountaineering establishment, not least for his success as a bestselling author.

"They were afraid of being thought boastful, but Frank wasn't," Tony Smythe says. "His publisher Victor Gollancz really influenced him. Gollancz warned him that if he just wrote for climbers he'd never get back a fraction of his advance. Frank saw that. He didn't hesitate. From that moment he said, sod you, I'm going to publish my books and get publicity and promote myself."

Frank also had a tendency to provoke feuds. He fell out with the physiologist Thomas Graham Brown, with whom he did his most famous Alpine climbs. John Hunt, a friend and leader of the 1953 Everest team, described Frank as "a sensitive soul, touchy, impulsive and petty at times". Tony Smythe agrees: "He was very touchy and would easily offend."

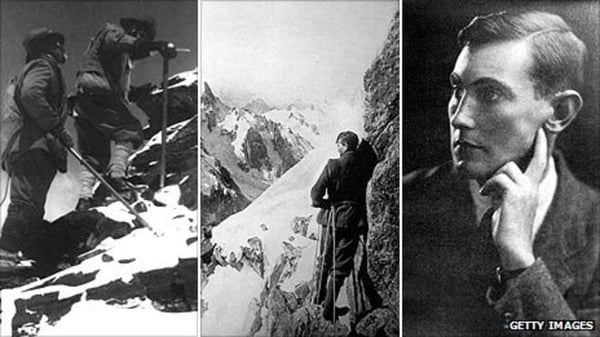

George Mallory and Andrew Irvine in June 1924. This is believed to be the last image of the men before they disappeared. Photograph: AP

George Mallory and Andrew Irvine in June 1924. This is believed to be the last image of the men before they disappeared. Photograph: AP

Tony Smythe's book, My Father, Frank, published by Bâton Wicks – part biography, part memoir – became, he says, "a voyage of personal discovery. I became more and more engrossed in finding out about this man who I knew very little about." His father left his mother Kathleen in 1938 for Nona Guthrie, whom Smythe met at the home of his close friend Sir Francis Younghusband, the imperialist adventurer. "My mother didn't blame him at all. She was a rather self-sacrificing person who put herself out for others. We felt disappointed we didn't have a dad, but that's the way it was and we got on with things."

Frank Smythe died of cerebral malaria at the start of an expedition to the Himalaya in 1949. Nona later married the Earl of Essex and, irritated by demands for access to her late husband's archive, burned his photographic negatives and other material.

Tony Smythe has no doubt what his father would think of the modern Everest scene, and the fight that took place on the mountain this spring: "He would have been horrified by the whole thing – the razzmatazz and the vast numbers going up there. I went to a talk by [Everest guide] Kenton Cool the other night. Fabulous guy, hugely outgoing, loves Everest, but the opposite of Frank in his view of the mountain. Frank was somebody who saw the spiritual side of the mountains and he really would have been appalled."

This article first appeared on http://www.theguardian.com. The original can be read here.