Daily Mountain

48 years, Australia

Purja Launches New K2 Push — But How Risky Is It?

This article first appeared on http://explorersweb.com. The original can be read here.

Turns out that it’s not over on K2. While most big teams have called off their expedition because of the extreme avalanche danger near the summit, Nirmal Purja is leading a rope-fixing crew on a last-ditch attempt, closely followed by no-O2 climbers Adrian Ballinger and Carla Perez.

K2: still coveted, still wild. Photo: Seven Summit Treks

K2: still coveted, still wild. Photo: Seven Summit Treks

In related news, the end of the Savage Mountain could be at hand. By next year, K2 could become the Tamed Mountain, if Imagine Nepal carries out its plan to eliminate the most technical passages by installing ladders to the top. Essentially, it turns K2 into a via ferrata experience. The climbing community has swiftly reacted with an unanimous “WTF?”

Nims leads the way

In an unusually detailed report, Nirmal Purja has outlined his immediate plans on K2. For the sake of his larger project — all 14 8,000’ers in a single year — he won’t give up on the mountain yet, despite the risk.

Already in Base Camp, Nims will lead five rope-fixing Sherpas to try to finish the job they began last week. If all goes well, they will reach the summit on July 24. “I could have gone to Broad Peak [first] and then returned to K2, but there’s a lot of hope in my team, hence I’m heading [up now],” Purbal wrote. “At Base Camp, the remaining climbers stayed only because they thought my team had a chance of fixing ropes to the summit.”

Art, or rinky-dink ink? Nirmal Purja exhibits his commitment to the 14 8000’ers

Art, or rinky-dink ink? Nirmal Purja exhibits his commitment to the 14 8000’ers

He added realistically: “If I said I’m not nervous about leading the summit-fixing team on K2, then I’d be lying. I have seen the video clips and the images and I’m fully aware of the risks. I also know that some great climbers, whom I look up to, have given up.”

“My career within the UKSF/SBS [military special forces] has taught me so many things. I’m used to taking risks.”

Purja’s ambitious project is on schedule so far. He has notched nine peaks and K2 would mark his tenth and most difficult so far. From Camp 2 today, he plans to reach C4 tomorrow. Then his team will start fixing ropes from 10pm on July 23.

Joining Purba are Lakpa Dendi Sherpa and Gasman Tamang from his own Project Possible team, plus Changba Sherpa and Lakpa Temba Sherpa from Seven Summit Treks. An international group of clients from Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Germany, the United States, Poland, Austria and Brazil, with their personal Seven Summit Treks guides and porters, will follow on July 25.

The No-O2 climbers – notes on motivations and cooperation

Before this big group, but after Purba’s fixing team, U.S. guide Adrian Ballinger and Ecuadorian Carla Perez will be looking to enter the list of K2 summiters with the golden tag, “No O2 ascent.”

Perez moved to Camp 2 yesterday with Esteban Mena (who will use oxygen on the upper sections). Ballinger remained in Base Camp an extra day but will join his mates at Camp 3 today. From here, they will advance to Camp 4 on July 23 and aim to summit on July 24, the same day as Purba.

Carla Perez (middle) with Esteban Mena (right) and a Sherpa team member at left. Photo: Adrian Ballinger

Carla Perez (middle) with Esteban Mena (right) and a Sherpa team member at left. Photo: Adrian Ballinger

Ballinger has posted a long, enlightening report about the summit plans, logistics and motivations of all involved:

“The weather forecast is reasonable … We are joining forces with Nims to see if together, we can unlock the code of the traverse, reportedly buried in deep, unstable snow. Nims and his Sherpa team have added a great influx of stoke and strength, just as 90% of climbers left the mountain.

“With Carla and I attempting without oxygen, we know we will not be much help opening a route through deep, unconsolidated snow, never mind fixing ropes for others. While our support crew (on bottled oxygen) are ready to do the backbreaking work of breaking trail, Nims and his team, also on bottled oxygen, have requested first shot at the slope above the Bottleneck. What can I say? They want it, and it helps Carla and I hugely! So we will be ready to jump in with our team’s strength and experience, [but] hold back and let their team take first crack. I’m honored to share the mountain with a strong, motivated crew, and can’t wait to help in any way my inevitably shattered body will allow.

“Climbing without oxygen requires a whole lot of humility, a lesson beaten into me three years ago on Everest. I will happily take a backseat on this summit push.”

The Outfitter’s point of view

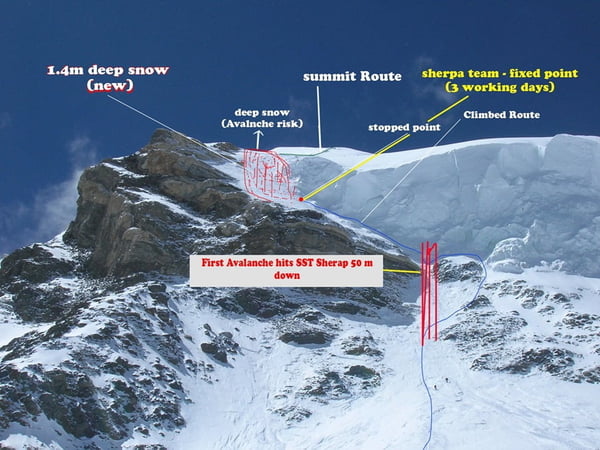

SST owner Mingma Sherpa remains hesitant about whether conditions will improve on the mountain. “K2 is not ready,” he said last week. Today, the businessman and 2004 K2 summiter explained the wind/snow interplay in more detail:

“If you want K2 with less snow (and therefore more climbable), then you need high jet stream winds before a summit push, because that will swipe away all the fresh, soft snow above 8,000m,” he said.

Mingma Sherpa’s illustration of last week’s summit push on K2. Photo: Seven Summit Treks

Mingma Sherpa’s illustration of last week’s summit push on K2. Photo: Seven Summit Treks

Mingma admits that the weather on K2 is unpredictable and that the climbers’ decision to launch a second summit push is rational and demonstrates that new generations “have all sorts of knowledge regarding safety.”

Kari Kobler, manager of another big team who called their previous attempt off at 8,400m, is less optimistic about this latest move to push things beyond what those following professional risk management are comfortable with.

“Our lead guide, Max Berger, was a long-time IFMGA instructor … and his assessment was very clear,” said Kobler. “Berger and other professionals on the mountain agreed that the situation will not improve with a couple of days of good weather but only when this slope is triggered. Trying it anyway is high risk for the fixing team and for all climbers following … Let’s keep fingers crossed for those who want to give it a try nevertheless.”

Stairway to the summit?

Imagine Nepal was one of the groups that called off their attempt on K2 because of safety concerns. As a Plan B, they have moved 10 climbers to Gasherbrum II, where they will launch a summit bid asap. Meanwhile, the outfitter has aired an idea to lessen future risk for its clients: Use ladders to turn the upper, most exposed sections of K2 into a sort of via ferrata.

“We will prepare with ladders, a drill machine and bolts to follow the rocky route which is almost 100% safe,” the company enthusiastically states. Apparently, someone in “Garrett’s team” (Madison Mountaineering) floated the idea, which has its origins after an old 1939 attempt.

The news quickly spread through social media and triggered an avalanche of responses, virtually none of them favorable.

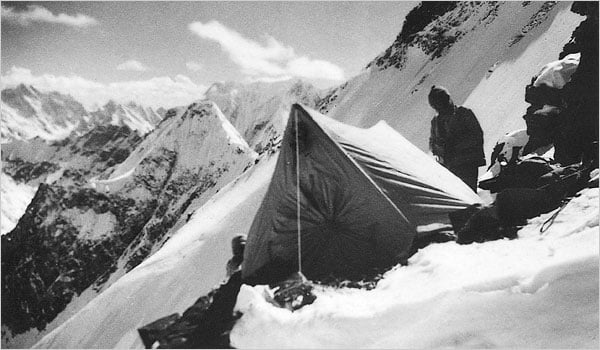

Historical background: In 1938, Charles Houston led the first American Karakoram expedition. Their members explored several routes, managed their way up the House Chimney and made it as far as 7,500m, still well below the Bottleneck. They also mapped the Abruzzi Spur as the best potential route to the summit. Sixteen years later, in 1954, the Italians did, in fact, achieve the first ascent of K2 via that route.

Camp 4 at 6,500m back in 1939. At that time, Camp 4 lay below the House Chimney. The expedition planned nine higher camps before the summit. Photo: Fritz Wiessner Collection

Camp 4 at 6,500m back in 1939. At that time, Camp 4 lay below the House Chimney. The expedition planned nine higher camps before the summit. Photo: Fritz Wiessner Collection

Fritz Wiessner led a second American expedition in 1939. The accomplished Wiessner did climb the rocky outcrops on the left. The feat took him nine hours of unprecedentedly difficult climbing at that altitude. After that hair-raising section, his Sherpas insisted on retreating, despite the fact that the way to the top was straightforward from that point. The expedition ended up in tragedy with four dead. In the ensuing controversy, survivors blamed each other, and subsequent expeditions shelved the idea of difficult, exposed rock climbing at that altitude.